Celebrating Hong Kong's most historic trees

There aren’t many cities in the world where trees regularly make the news. But trawl the archives of the South China Morning Post and you won’t have to go back far to find stories on an arboreal theme. ‘Time running out to save historic tree .’ ‘Axe falls on decades-old banyan trees in Hong Kong after stand-off .’ ‘Worst post-typhoon tree situation .’

Trees – especially the historic banyans which entangle themselves with the city’s masonry – are part of Hong Kong’s fabric and consciousness. The clean-ups after the annual typhoons that threaten the island and uproot its forests are accompanied by prolonged bouts of soul-searching: are we doing enough to protect our trees? Do we care enough about this part of our natural heritage?

So it’s timely that a book celebrating Hong Kong’s 390 native tree species is about to be published.

A local botanical artist, Sally Grace Bunker , has collaborated with two botanists from The University of Hong Kong, Professor Richard Saunders and Dr Pang Chun-chiu. The result is Portraits of Trees of Hong Kong and Southern China.

The work highlights over 100 species that are illustrated in watercolours. We have chosen seven trees worth celebrating in their own right, but also because they tell us something about the natural and human history of this extraordinary place. Most of them grow widely throughout the territory, whether in the hinterland of Hong Kong’s biggest island, Lantau, or labelled and curated in Central’s Botanical Gardens.

The selfish tree

Acacia confusa (Taiwan acacia) wasn’t originally a native species but has now been extensively cultivated as it grows well in degraded areas and helps to prevent soil erosion. As it’s relatively fire-resistant, it’s also widely cultivated in Hong Kong as a fire break in plantations. The tree is known to excrete toxic chemicals into the soil following the rotting of fallen leaves; these chemicals act to inhibit or suppress the growth of other plants. This phenomenon – known as allelopathy – is beneficial to the tree itself as it reduces below-ground competition for nutrients and water, but is an undesirable characteristic in a plantation species as it hinders natural regeneration and biodiversity restoration.

Credit: Sally Grace Bunker

An awkward symbol

Bauhinia blakeana (Hong Kong orchid tree) was first found growing in the grounds of an abandoned house near Mount Davis, Hong Kong Island, in the late 19th century and was later introduced to the Hong Kong Botanic Gardens. This individual (which survived being blown over by a severe typhoon in 1906) was propagated and became the ancestor of all specimens cultivated today.

The Bauhinia blakeana is an artificially propagated hybrid derived from interbreeding two naturally occurring species, Bauhinia purpurea and Bauhinia variegata. Bauhinia blakeana was adopted as the floral emblem of Hong Kong in 1965, and now appears, often in a stylised form, on local banknotes, coins and the SAR flag.

Credit: Sally Grace Bunker

The devious tree

Adenanthera microsperma (red sandalwood) is common in feng shui woods near villages in Hong Kong. The fruit pod is large, up to 20 centimetres in length, and splits into two valves as it dries, exposing bright red glossy seeds that are suspended from the pale brown inner surface of the pod. These seeds superficially resemble fleshy berries and it has been suggested that the red colouration has evolved to mimic berries and deceive birds that normally eat fleshy fruits – a clever method of seed dispersal.

Credit: Sally Grace Bunker

The tree that gave a city a name

Aquilaria sinensis (incense tree) is the source of a highly fragrant, resinous wood – known commercially as agarwood – that’s used in the manufacture of incense and as a source of Chinese medicine. The high concentration of resin develops in response to fungal infection, with uninfected trees lacking the valuable resin. Mature individuals of Aquilaria sinensis are often indiscriminately and illegally felled in Hong Kong in the hope of retrieving commercially valuable agarwood.

Hong Kong was historically an important hub in the commercial export of Aquilaria sinensis incense to other parts of Asia, with most exported via Shek Pai Wan in Aberdeen. This harbour was known as Heong Kong (meaning ‘Incense Harbour’), which was subsequently misapplied as ‘Hong Kong’ to the entire territory.

Credit: Sally Grace Bunker

The great survivor

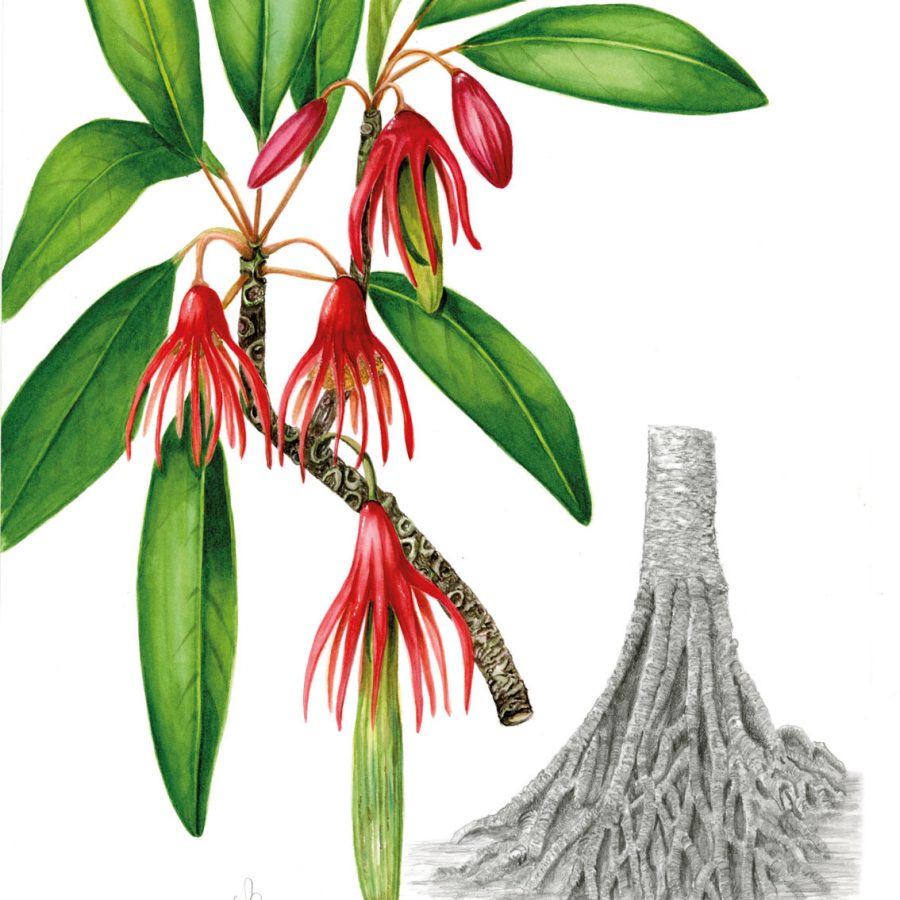

Bruguiera gymnorhiza (many-petalled mangrove) is one of only eight plant species in Hong Kong that are truly adapted to survive in mangrove habitats. Mangroves are intertidal ecosystems and, as a consequence, the high salinity of the habitat is extremely challenging for plant survival.

Many of the morphological peculiarities of mangrove trees are adaptations to surviving in these difficult conditions, including ‘prop’ roots that help support the tree on soil that is unstable because of the tides; roots with ‘knees’ that project above the ground to assist with aeration in oxygen-poor soil; and the evolution of vivipary, in which seeds germinate while still attached to the maternal plant.

Credit: Sally Grace Bunker

The coloniser

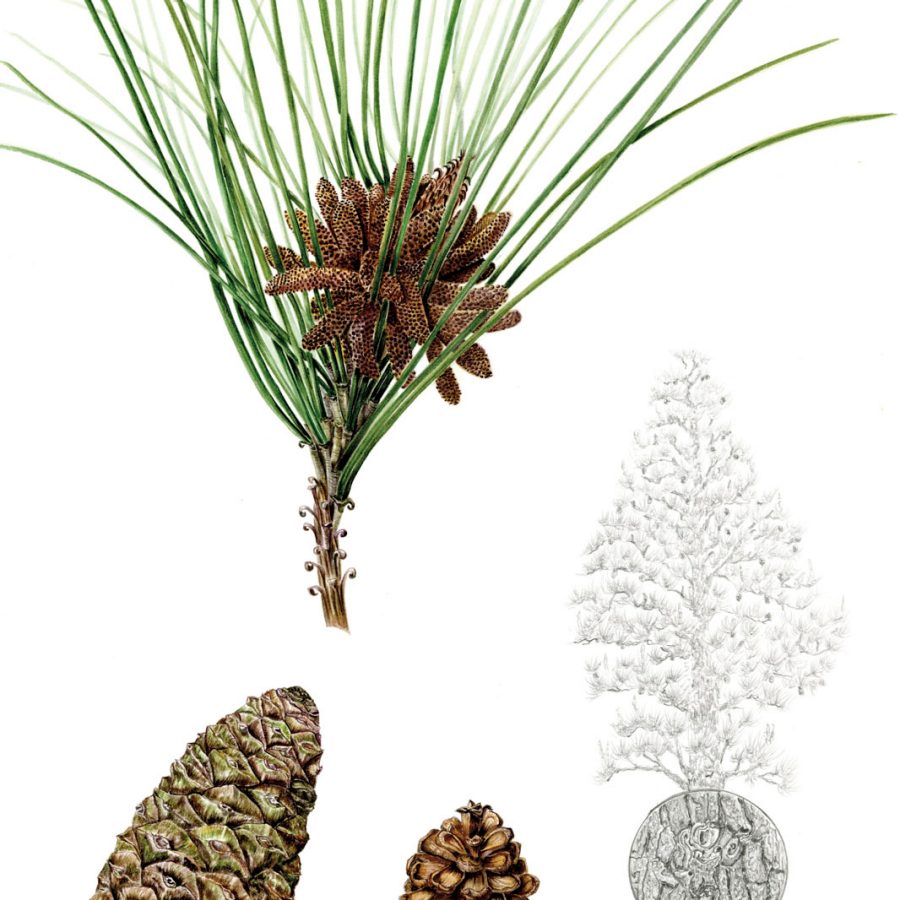

Pinus massoniana (Chinese red pine) is Hong Kong’s only native pine species. The British government implemented several major afforestation projects (from the early 1870s until the Second World War, and again from 1953), with Pinus massoniana the most widely planted species. Concern was raised in 1978, however, by the death of many trees following the wilting and browning of needles. This was due to ‘pine wilt disease’, resulting from infestation by roundworms spread between trees by longicorn beetles originating from North America. This, in addition to a scourge of pine-needle scale insects from Taiwan, China, caused the widespread destruction of local Pinus massoniana populations, dramatically reducing the extent of forested land in Hong Kong.

Credit: Sally Grace Bunker

The left-behind tree

Pyrenaria spectabilis (common tutcheria) is a rare local species that is now legally protected. It is dispersed by ‘scatter-hoarding’ rodents that collect and store fruits to eat later. The seeds often germinate when the rodent fails to retrieve the fruit.

The bad news: these rodents no longer survive in Hong Kong and, as a consequence, tree species with this dispersal mechanism are rare and noticeably absent from secondary forests. This is in striking contrast with the closely related species, Polyspora axillaris, which produces winged seeds that hitch a ride on passing breezes. As a result, Polyspora axillaris is far more common in Hong Kong, and is regarded as a pioneer species that is able to colonise disturbed areas and often dominates early-stage secondary forests.

Hero image: Sally Grace Bunker

Hong Kong travel information

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English