Keeping up with formidable traveller Isabella Bird

For much of the 19th century, Isabella Lucy Bird sought out the furthest corners of the world, dashing off bestselling travelogues, wielding her cumbersome photographic equipment with patience and skill, and founding hospitals and orphanages, all the while undaunted by persistent sciatica and spinal complaints and shrugging off accidents and occasional attacks by hostile natives. She was a supremely eminent and highly admirable woman at a time when well-born English ladies were supposed to have few ambitions beyond matrimony and motherhood.

Credit: Royal Geographical Society / Getty Images

Credit: The Picture Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo / Argusphoto

She did marry – Edinburgh surgeon John Bishop – but he died five years later, leaving her well-off. Single, full of fancies and with a boundless thirst for knowledge inherited from her polymath mother and her father, a barrister turned clergyman and keen amateur botanist, she set forth in earnest once again.

Most of the time she travelled solo. Interpreters, porters and the like were a necessity, but she didn’t feel the need of a chum. Once – armed with medicine chest and revolver – she joined forces with a British military expedition across the desert from Baghdad to Tehran, but this wasn’t because she thirsted for human company: she just fancied the adventure.

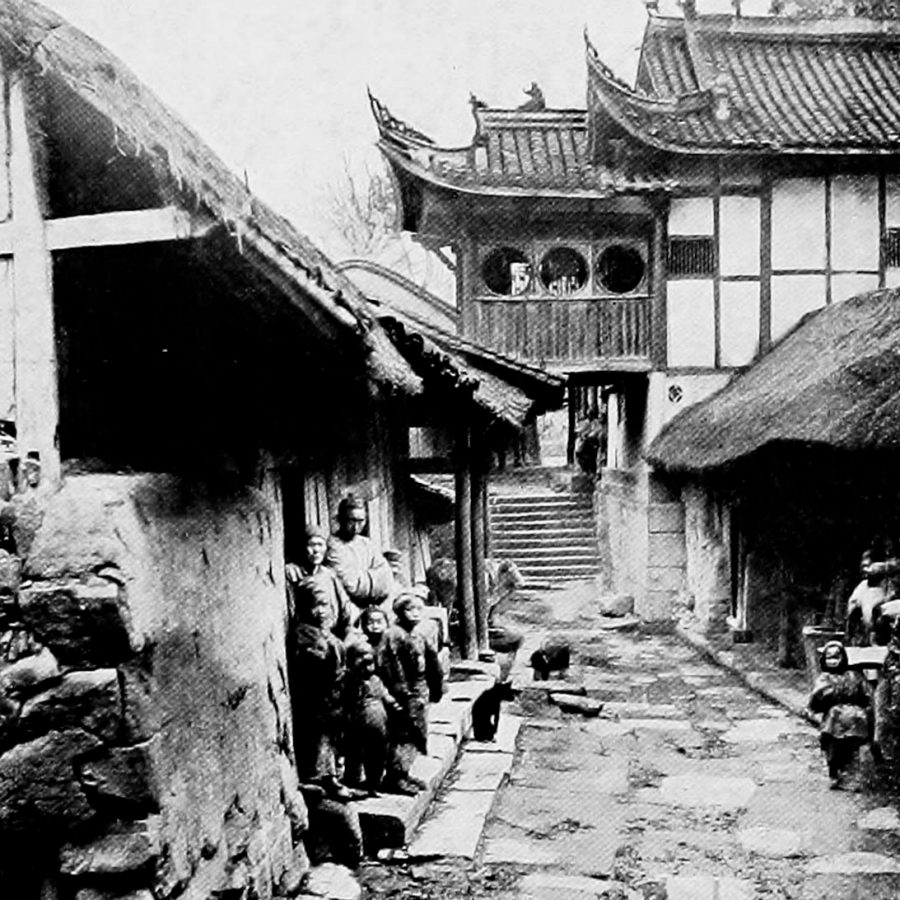

Wherever Bird travelled – America, Asia Pacific, Arabia – it would not have been easy going. Even assuming that I’d have been allowed to tag along, I’m not sure how much use I’d have been. I could have strapped up her broken ribs after she fell from her horse fording a river in Ladakh, India, but I’d have been quaking in my boots when a mob tried to set fire to the house where she was staying in Sichuan, China (a posse of soldiers turned up in the nick of time). I doubt I could have added much to the charm she exercised on the Maharajah of Kashmir to donate the land she wanted for a hospital, nor would I have had the patience to sit through the meetings to set up orphanages – even if I had been able to speak Korean or Japanese. I certainly wouldn’t have proved much of a rival to the one-eyed, poetry-loving desperado Rocky Mountain Jim, to whom she briefly lost her heart (but not her head) in Colorado.

I picture myself and Bird sitting across the campfire at night, her knitting, me trying to think of a good conversational opener. After all, this was the woman who tartly declared: ‘I still vote civilisation a nuisance, society [specifically Britain’s stuffy middle-class milieu] a humbug and all conventionality a crime.’

Bird’s default setting was ‘off the beaten track’. It wasn’t sufficient to sail halfway round the world to Japan – she wanted to visit the archipelago’s original inhabitants, the Ainu, in northern Hokkaido. And she did. Small wonder that in 1892 she was invited to join the Royal Geographical Society, which had been chaps-only since its establishment 62 years earlier.

Credit: Royal Geographical Society/Getty Images

In 1904, aged 72, Bird died pretty much as she had lived – not quite in the saddle, but in Scotland following a solitary jaunt riding a black stallion (a gift from the Sultan) across Morocco. She left £33,000 in her will – about £4 million today (HK$41 million) – testament to the popularity of her books. Still fresh and inspirational, reading them is pretty much like travelling beside her, which is probably as close as I should ever aspire to get.

Oh, and it’s worth noting that the John Bishop Memorial Hospital she founded in Anantnag, Kashmir, still stands today, more than a century after admitting its first patient.

Hero image: Royal Geographical Society / Alamy Stock Photo / Argusphoto

More inspiration

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English