How to explore Los Angeles without a car

In May 2016, as petrol prices rose throughout California, a billboard for the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transportation Authority – Metro for short – appeared in one central neighbourhood.

The image was simple: a woman’s arm handcuffed to a petrol pump, with the message: ‘Free yourself. Go Metro.’

The city (and the county) have prioritised light rail and rapid bus routes since the Blue Line – which travels from LA’s city centre to Long Beach – began running trains in 1990. In the same month the billboard was erected, Metro opened the extension of the Expo Line, restoring rail service between central LA and Santa Monica for the first time in more than 60 years.

Still, public transport remains a complicated sell in LA, famously a city of the car. After all, that Metro billboard is geared towards drivers, which suggests how much of the new LA is rooted in the structure of the old. Plus, the intersection at which it went up – the so-called Fairfax Asterisk – still won’t have a rail link for three years.

But is it possible to get around LA without a car? That’s been a subject of debate for 50 years.

In his 1973 essay Autopia, Dutch travel writer Cees Nooteboom frames it this way: ‘With their cars, Angelenos go places, they travel infinite numbers of kilometres in a world that continuously remains Los Angeles. Cars do not designate a lack of freedom but rather freedom itself.’

Credit: Hayk Shalunts / Shutterstock; Others: Yuri Hasegawa

If this were true in the 1970s, it is much less so today. Southern California drivers often find themselves confronting a rush hour that lasts the entire day.

But to see that LA is in a state of transformation, all you have to do is put your feet on the ground.

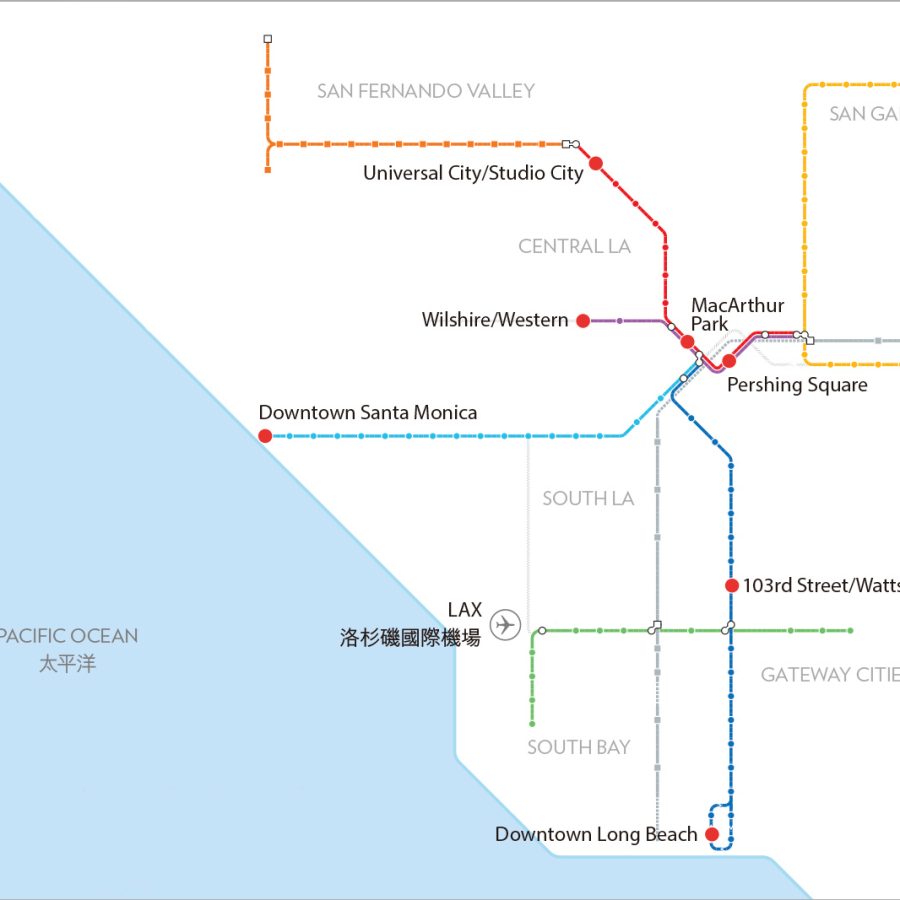

Beginning with the opening of the Blue Line, Metro has built 170 kilometres of track (more than Chicago’s El or the San Francisco Bay Area’s Bart system) on six different lines. In late 2016, voters passed Measure M, a sales tax increase predicted to raise US$120 billion (HK$936 billion) that will help fund a number of rail projects over the next 40 years. This means the construction of two new lines: the Crenshaw and the downtown regional connector, as well as the expansion of three existing ones. Examine a map of what the system will look like in 2040 and you begin to see a comprehensive system.

The irony is that this forward planning is also a return to the LA of a different time. A hundred years ago, the Pacific Electric Railway Company operated an enormous trolley system, with more than 2,100 trains running daily along 1,600 kilometres of track. Nostalgics like to point out that the new lines – the Blue and Expo, the Gold and Crenshaw – follow old Pacific Electric rights of way. It’s a reminder that, when it comes to the life of cities, everything old can be new again.

Credit: Yuri Hasegawa

Nowhere is this clearer than the present system, which has helped rejuvenate central LA. Of the six rail lines, five run through the city centre, which has re-emerged as a social and cultural hub. To explore LA by rail, it makes sense to start here: at Union Station, perhaps, where the Red, Purple, and Gold lines stretch to Pasadena, East Los Angeles and North Hollywood; or a mile south, at Metro Center, where the Red and Purple lines connect with the Blue and Expo, offering access to Long Beach and Santa Monica.

In the course of one long day I rode the entire system: all 93 stations.

I found myself in Azusa, Universal City, Redondo Beach; from the San Gabriel Valley to the San Fernando Valley to the South Bay. For visitors, the appeal may be more specific: from Metro Center, you can take the Red Line to the heart of Hollywood; the Expo Line to the beach. Travel in the other direction and the Blue Line brings you to the Watts Towers, the magnificent monument Simon Rodia spent 30 years erecting. Or take the Purple Line to MacArthur Park and visit Langer’s Delicatessen, a local classic.

Credit: Yuri Hasegawa

Transport makes a city – or remakes it, in the case of LA. A century ago, when most of this place was still undeveloped, communities grew up around stations on the Pacific Electric lines. Today, the challenge is more difficult because the city has been built. These new lines must conform to the landscape that surrounds them, rather than the other way around.

‘We’re playing catch-up,’ explains Los Angeles Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne, ‘building this system through the teeth of the built-out city.’ It’s remaking a landscape that already has an identity and shape.

Autopia was an idea Nooteboom borrowed from Reyner Banham, the British architectural historian. Yet even Banham realised that such a designation ‘offers a misleading truth because it is persistently interpreted as referring only to automobile transport, and that interpretation is so trivial and so shallow historically’. What he was saying is that LA is a young city; that we need to give it time to grow.

This is what the rail system signifies: a way to reimagine LA while also reconnecting to its history, of ‘going back to the future’, in mayor Eric Garcetti’s phrase.

How far can you travel without getting in a car? With the Olympics coming in 2028, many of Metro’s new projects have been fast-tracked. It is a cliche of LA that the city is always in transition; always looking to reinvent itself. But that doesn’t mean the rail system is not a shift in how the city regards itself.

‘Why this is a revolution,’ Hawthorne suggests, ‘is that, if you take the train or bus, you’re paying attention in a different way to the physical design of the city. You’re connected more directly to the public realm.’

7 special experiences on the train network

Aquarium of the Pacific

Station: Downtown Long Beach

The Aquarium of the Pacific houses 500 species of sea animal, drawing around 1.5 million visitors annually. While in Long Beach, you can also visit the Queen Mary, an ocean liner that has been docked nearby since she retired in 1967.

Angels Flight Funicular

Station: Pershing Square

Built in 1901 and reopened in 2017, the so-called World’s Shortest Railway runs just 90 metres from Grand Central Market in LA’s city centre to the top of Bunker Hill.

Langer's Delicatessen

Station: MacArthur Park

Open since 1947 on the corner of MacArthur Park in the Westlake district, Langer’s was on the verge of going out of business before the Red Line opened in 1993. Since then, it’s been rejuvenated by diners making the short (five-stop) train ride from central LA.

Santa Monica Pier

Station: Downtown Santa Monica

One of the last amusement piers in Southern California, this iconic location features food stalls, a video arcade, the small but wonderful Heal the Bay Aquarium and an amusement park with a vintage 1920s carousel.

Universal Studios Hollywood

Station: Universal City/Studio City

One of the oldest studio lots in Southern California, Universal began offering tours in 1964 and opened its first theme park attraction the following year. Now, it is a fully-fledged amusement park, with rides based on popular films such as the Harry Potter franchise and TV shows like The Simpsons, and the outdoor Citywalk mall.

Watts Towers

Station: 103rd Street/ Watts Towers

One of Los Angeles’ most iconic landmarks, the Watts Towers were constructed by local homeowner Simon Rodia on his property. After Rodia completed the towers, he left Los Angeles but the towers – constructed out of concrete and found objects (tiles, bottle caps, porcelain) – continue to stand over the neighbourhood.

The Wiltern

Station: Wilshire/Western

Opened in 1931, The Wiltern theatre is one of the art deco jewels of Los Angeles, a blue-green terracotta-tiled building angling back from the southeast corner of Wilshire Boulevard and Western Avenue in Koreatown. It’s a prime venue for live music, but also worth visiting as an architectural masterpiece.