Enlightened explorer: Travels with Alexander von Humboldt

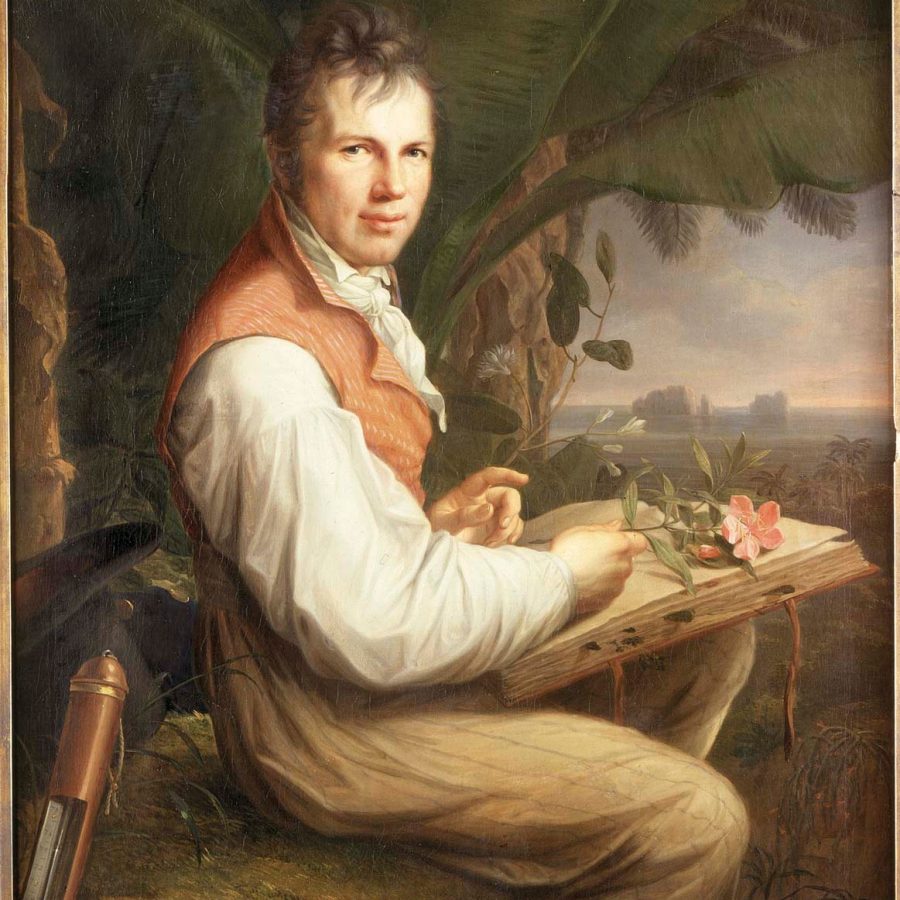

He was certainly eccentric and at times he could be irascible. But the Prussian polymath-turned-explorer Alexander von Humboldt had such a razor-sharp brain – and revolutionary way of thinking – that he would have been a travelling companion unlike any other.

Born in 1769 into a prominent Berlin family, Von Humboldt had the advantage of a top-notch Enlightenment education. The turning point in his life came when he was just 20: he met Georg Forster, a naturalist who’d crossed the uncharted Pacific Ocean on Captain Cook’s second voyage.

Young Von Humboldt was fascinated by Forster’s account of the Pacific and would’ve sailed on the next available voyage of discovery, had it not been for his needy mother. Only when she died in 1796 was he finally free to make his first major expedition outside Europe: a five-year trip to South America.

Credit: Ullstein bild via Getty Images

As he hacked a passage through jungles and mangrove swamps, Von Humboldt’s true genius was revealed. Nothing escaped his notice: tropical seeds, monsoon rainfall and tectonic geology – he studied and analysed everything.

And this is the point at which I would have joined him on his travels, helping him to paddle up the muddy backwaters of the Orinoco. In this vast river, he first saw electric eels – massive ones – with a shock so powerful they could kill.

Von Humboldt’s goal was to catch one, using his expedition horses to lure them to the riverbank. He then dissected them and, with his findings, developed a wholly new way of looking at electricity.

Travelling with Von Humboldt would have been physically exhausting. He carried barometers, thermometers and sextants and collected vast sacks of seedpods. He also uprooted plants and carried them to the coast, from where they were shipped back to Europe. Of the 6,000 species he sent home, one third were previously unknown.

After helping him paddle up the Orinoco, I’d have had to scale the snow-capped Andes and clamber the near-vertical ridges of Mount Chimborazo – Ecuador’s highest peak. Such gruelling treks were never gratuitous: in the case of Mount Chimborazo, he wanted to study the region’s flora and fauna at different altitudes and climactic conditions.

As he read through his botanical notes (with me as his assistant), he began to view the natural world in a radically different light from his contemporaries. He realised that the old scientific classifications failed to acknowledge that every species was part of an interconnected ecosystem. ‘In this great chain of causes and effects,’ he wrote, ‘no single fact can be considered in isolation.’

Credit: Peter Weller/ullstein bild via Getty Images

That one sentence was truly radical: Von Humboldt had just invented the web of life, the concept of nature that we know to this day. It was a turning point in the history of the natural world.

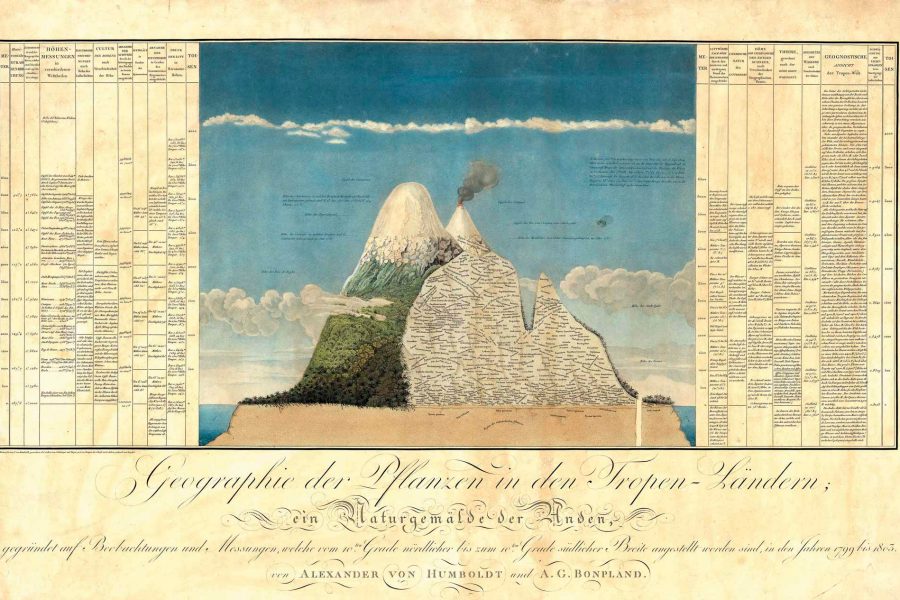

For Von Humboldt himself, the most precious product of his South American expedition was his Naturgemälde – a huge pencil sketch of Mount Chimborazo in cross-section. It showed the types of flora and fauna that could be found at different altitudes, while the side-columns gave details of atmospheric pressure, humidity and temperature. This information could then be compared with adjacent panels showing all the great mountains of the world. Its cross-referenced data was a graphic display of how the natural world was one vast global system.

Von Humboldt was to make many more expeditions – to Venezuela, Mexico and elsewhere – before dying at the ripe old age of 89. As the world’s first proponent of climate change, he would be appalled to learn that Venezuela’s Humboldt Glacier, named in his honour, is now melting into the sea.

Hero image: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo / Argusphoto

More inspiration

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English