How the Lei Yue Mun waterfront reflects old-time Hong Kong

South of the Kai Tak Cruise Terminal and overlooking the narrow stretch of water that marks the eastern approach to Victoria Harbour, at Lei Yue Mun – a sprawling hamlet anchored by a centuries-old Tin Hau temple – Hong Kong takes a step through the looking-glass.

Most visitors come here to revel in the raggle-taggle strip of seafood restaurants, but exploring Lei Yue Mun (‘Carp Gate’) a bit further grants a window into a way of Hong Kong life that might have sprung from a sepia-tinted photograph of yesteryear.

The merriest way in is aboard the Coral Sea ferry , a two-decked converted wooden fishing smack that putters back and forth from Sai Wan Ho on Hong Kong Island. Nine dollars and as many minutes lead to the pier at Sam Ka Tsuen. Once ashore, it’s but a brief walk to Lei Yue Mun itself: gloriously higgledy-piggledy, endlessly entertaining and bursting with character.

Credit: Derry Ainsworth

The scene is far removed from Hong Kong’s received image of a high-rise global financial hub. Single-storey houses seem to wrap themselves around the bulky granite boulders that festoon the landscape, rising up to the 222–metre escarpment called Devil’s Peak, and the maze-like layout is enough to make urban planners contemplate a different career. Old men loiter in the shade comparing the relative merits of their pet birds that are suspended in cages in the branches overhead; their grandsons and great-nephews – nonchalant, brawny youths stripped to the waist, the better to show off their tattoos – propel trolleys groaning with merchandise back and forth; schoolchildren hurtle in and out of the throng and an occasional wedding party, bride and bridesmaids holding their gowns up to the knee while keeping a firm hold of their smartphones, makes its way to the banqueting hall that stands hard by Lei Yue Mun’s bonsai lighthouse.

Credit: Moses Ng

Food has traditionally been the prime draw here, specifically seafood. For pretty much every restaurant along the zigzag alleyway that runs parallel to the shore, there’s a fishmonger’s stall, with an array of tanks filled with veritable academies representing all the bounty of the ocean: yellow tail, prawns, crab, lobster, sea cucumber, eel and even more exotic creatures that look as if they could have been hauled out of the furthermost recesses of the Mariana Trench. The modus operandi runs as follows: find some fish that take your fancy, agree on a price – a sometimes extended and seemingly over-elaborate process – and then take it to a restaurant (who’ll charge a modest cooking fee), preferably one with a marine panorama and – assuming the weather’s cooperating – an outdoor terrace.

Credit left: Derry Ainsworth; right: Moses Ng

But there’s a great deal more to enjoy in this secluded corner of Hong Kong. Past the green-hued pillar box adorned with the British royal cipher from older times, and the basketball court that often as not is carpeted with circular wicker trays containing drying seafood – the hamlet’s most redoubtable structure, once the village school, has taken on a new lease of life.

Lei Yue Mun has hosted a school for the best part of the last 100 years, and in 1959 (when average weekly wages were HK$42) Chan Kam-chi, the wife of Tiger Balm founder and philanthropist Aw Boon-haw, donated HK$15,000 for its expansion. Pupil numbers swelled to 500 at one stage but after young families moved away, the school closed in 2008. Two years later it reopened as Jockey Club Plus – part museum commemorating the Hakka folk who once worked Lei Yue Mun’s granite quarry, part activity centre, all capped by a neat rooftop cafe that opens at weekends.

Credit: Moses Ng

‘It’s heartening to see the building has taken on a new role,’ says Szeto Kin, a retired engineer who now runs Plus’ pottery classes.

‘Now it’s both children and adults who come here to learn, to work with their hands and try something new. Clay, like humans, has a character, and they learn how to shape it with gentleness and care.’

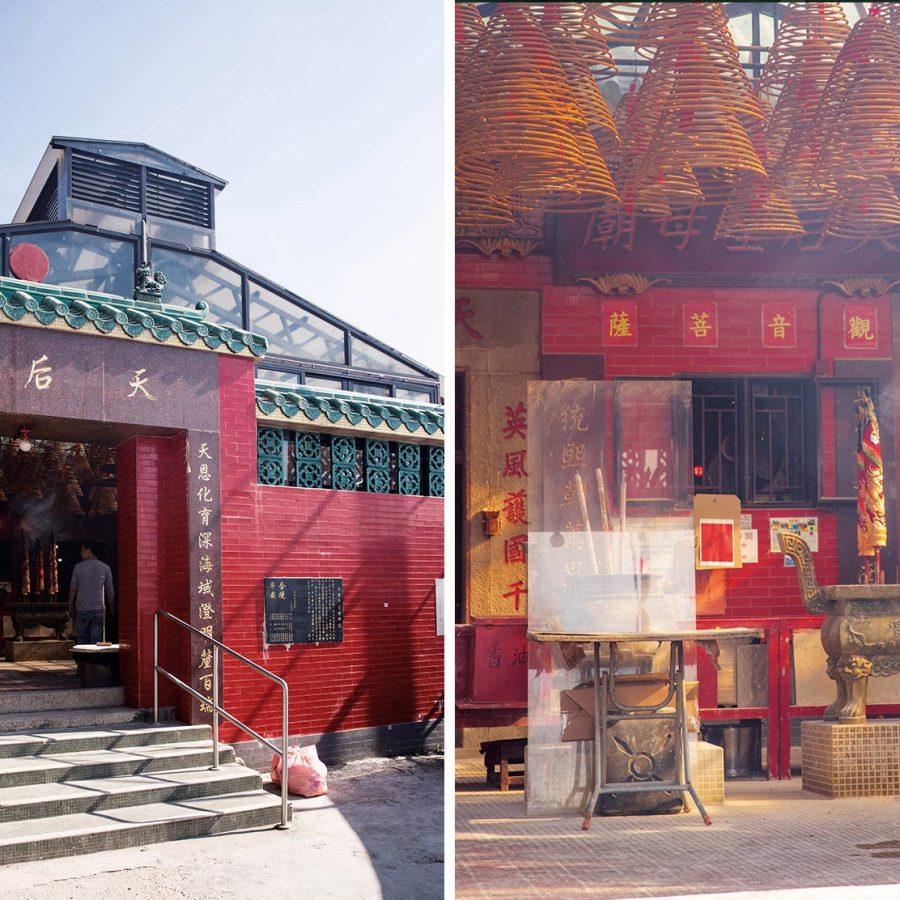

If Jockey Club Plus is Lei Yue Mun’s head and the seafood strip its belly, then the Tin Hau Temple that crouches by the water’s edge between looming phantasmagorical rocks is its heart and soul.

Beyond the 100-year-old Wishing Tree that promises succour for lost causes and a short way from the quarry where once Hakka labourers blasted and hammered, the temple’s ambience borders on the eerie, with eddies of smoke from the dozens of beehive-like coils of incense strung from the ceiling wafting around the effigies of Tin Hau, goddess of the sea, Guanyin, goddess of mercy, and other deities.

Credit: Derry Ainsworth

‘The temple was built in 1753, as many fishermen lived here then and they wanted the protection of Tin Hau,’ says Matthew Lau Ming-fat, the temple’s custodian.

‘But 200 years later my predecessor dreamed the goddess had told him to rebuild her temple. The village chief thought he was making it all up for his own ends, and refused to believe him. But then the custodian had a second vision, and the chief changed his mind.’

Credit: Derry Ainsworth

The temple’s been twice renovated since, defying the worst havoc threatened by summer typhoons and acting as a focal point for all of Lei Yue Mun and its extended family.

‘A lot of people come here every day, but thousands come at Lunar New Year, even from overseas, and again on Tin Hau’s birthday in April,’ says Lau. ‘The celebrations last for several days with Cantonese opera performances and a lot of feasting – seafood, of course.’

Credit: Derry Ainsworth

Immediately behind the temple, four bold red characters are inscribed on a rock beside a small pebbly beach. They read ‘hoi gok chiu yum’ – which might be translated as ‘The Cove That Dances to Music’. Blending the enigmatic with the poetic, and set against one of Hong Kong’s loveliest vistas, they’re an apt endnote to an excursion to Lei Yue Mun.

Credit: Derry Ainsworth

Did You Know…

Lei Yue Mun was once a thriving granite quarry: but when the government banned explosives, business dried up

Credit: Derry Ainsworth

Go Further

Devil’s Peak

A relatively easy hour-long hike from Lei Yue Mun, atop this hill two long-deserted gun batteries – named Gough and Pottinger – furnish a bleak reminder of the Battle of Hong Kong in December 1941.

The Wilson Trail

Opened in January 1996, the 78-kilometre Wilson Trail is one of Hong Kong’s best hikes, and a part of the footpath runs north from Lei Yue Mun towards Clear Water Bay.

Hong Kong Museum of Coastal Defence

Located on Hong Kong island, Lei Yue Mun fort (built in 1887) is now home to this airy, well-interpreted museum , with displays covering the past 600 years. Make sure to check out the torpedo slipway that opens out onto the harbour.

Hero image: Derry Ainsworth

Hong Kong travel information

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English