The Hong Kong airport story: then, now and the future

There’s a scene in the novelist James Clavell’s 1981 thriller Noble House where a swaggering American businessman named Lincoln Bartlett lands at Hong Kong’s old Kai Tak Airport. As he steps off the plane, he takes in ‘a strangeness on the wind, neither pleasant nor unpleasant, neither odour nor perfume – just strange, and curiously exciting’.

‘What’s that smell?’ he asks police superintendent Robert Armstrong.

‘That’s Hong Kong’s very own,’ he’s told. ‘It’s money.’

Today, it takes a little longer to sample the curiously exciting strangeness of Hong Kong. You emerge from the airport terminal building, not into one of the world’s densest urban environments, but onto a mountainous island in the South China Sea. But the winds of change – and the smell of money – still swirl around both the new Hong Kong airport and the old.

Both the old airport and its replacement, the sprawling Hong Kong International Airport on Chek Lap Kok, find themselves at the centre of multibillion-dollar development plans that will shape Hong Kong for years to come.

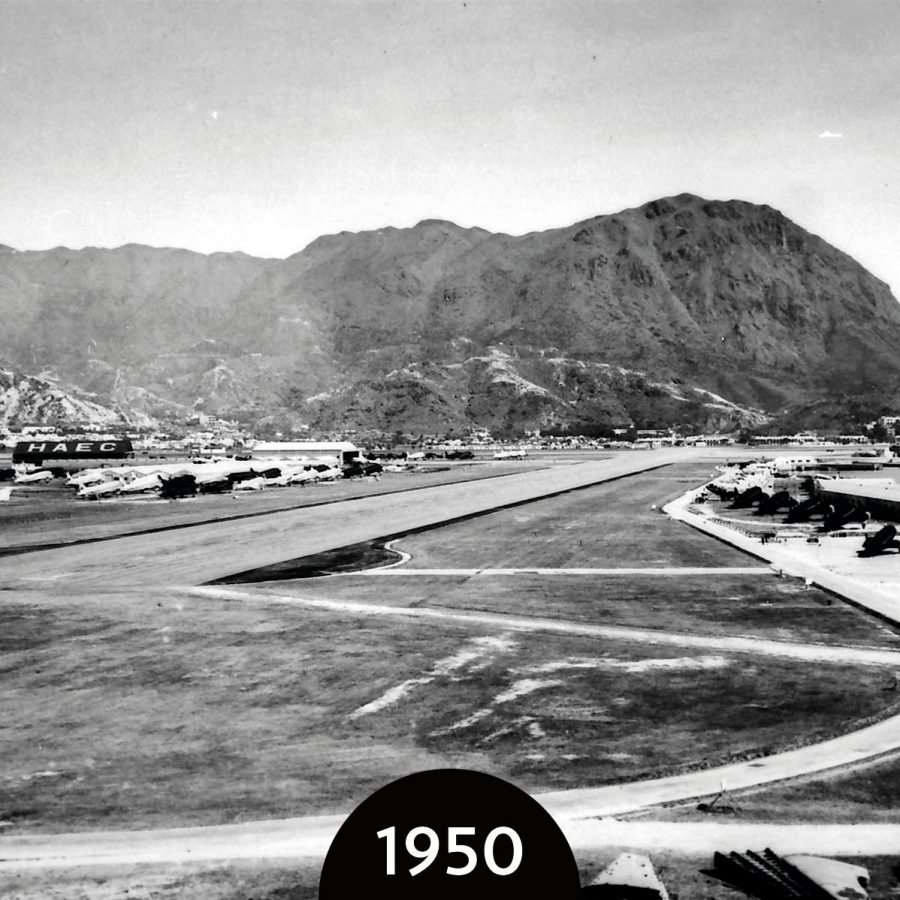

The history of Kai Tak goes back to 1912, when businessmen Ho Kai and Au Tak raised money to reclaim a swathe of land from Victoria Harbour. Their plan to develop the land failed and they were bought out by the British colonial government, which began using it as an airfield. It was gradually expanded and improved over the years until it began offering regular scheduled flights to cities around the world.

By the boom years of the 1980s, Kai Tak was taking on more flights than it could handle, and high-rise apartments and tenements had spread to within spitting distance of the runway. Anyone flying into the Hong Kong airport experienced the hair-raising approach that took them alarmingly close to rooftop antennae and drying laundry.

‘I remember landing at Kai Tak and seeing into a flat – a girl was brushing her hair by the window. It was that close,’ says former Hong Kong resident Fiona Hawthorne.

The new Sir Norman Foster-designed airport at Chek Lap Kok opened in 1998. It was the centre of an enormous infrastructure programme that included bridges, expressways, the Airport Express railway and vast land reclamation.

Moving the Hong Kong airport freed up 328 hectares of land at Kai Tak. In May, a plot of land at the former airport site became the city’s most valuable when developer Sun Hung Kai Properties paid a record HK$25.16 billion for it, to redevelop into flats. The former Kai Tak site will likely be the last large parcel of land to be developed in the heart of Hong Kong. After years of planning, the area’s master plan was finally put into place in 2007. It called for a large park, a sports complex, a cruise terminal, a hospital, hotels, housing, offices and retail, all of it built along a planned monorail line that will connect to the new Kai Tak MTR station, slated to open in 2020, and the former industrial neighbourhoods of Kowloon Bay and Kwun Tong, which have been rebranded as CBD2, a new business district.

‘There’s a lot of good stuff happening at Kai Tak,’ says Paul Zimmerman, co-founder of urban design watchdog Designing Hong Kong. Meant to be greener and more spacious than other parts of urban Hong Kong, Kai Tak will be centred along a park that runs next to the Kai Tak River, a former drainage channel that was initially meant to be capped and turned into a sewer.

After years of industrial pollution, the river gave off a powerful stench (perhaps what Lincoln Bartlett was actually smelling in Noble House) and it was all but devoid of life. But with new sewerage works and the city’s deindustrialisation in the 1990s, the water once again ran clear. Fish returned and so did birds. Community activists successfully lobbied to save the river, and the government is now adding greenery and a public promenade to its banks.

Architect Wallace Chang, who grew up next to the river and who helped lead the movement to save it, sees its integration into the former Hong Kong airport’s redevelopment as a way to build ‘a connection between the old and new neighbourhoods’.

When Kai Tak is fully developed in the mid-2020s, there will be enough housing for 90,000 people, whose flats will be cooled by an eco-friendly, district-wide seawater cooling system. More than 13 kilometres of cycle tracks will thread through the area. There will also be ample space to walk along the waterfront, including a promenade that has already been built along the former runway, which is now home to the Kai Tak Cruise Terminal – designed by Foster + Partners, just like Hong Kong International Airport.

Zimmerman’s chief concern is that Kai Tak will be burdened by too much big infrastructure. The cruise terminal’s already been criticised as a white elephant, since companies still prefer to dock at the more centrally located Ocean Terminal in Tsim Sha Tsui. Zimmerman also points to the Central Kowloon Route, a new expressway to Kai Tak, which will take over a large chunk of land for an interchange, potentially making the area a lot less pleasant and sustainable than its planners intended.

Until 1998, Chek Lap Kok was a bare and unimportant island in Hong Kong’s western waters. Then came the airport. Next comes one of the world’s most ambitious infrastructure projects.

The Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge on the north side of Lantau Island, right next to the Hong Kong airport, comes under immense development pressure. A new road link will eventually connect the airport to Tuen Mun in the New Territories, the Chinese mainland city of Shenzhen and other booming cities of the eastern Pearl River Delta. The Hong Kong airport will acquire a much-anticipated third runway and the existing terminals will expand.

‘I would say that with the shift of economic activity up and along the Pearl River Delta, development along [Lantau’s] north side towards Chek Lap Kok makes economic sense,’ says Zimmerman. But he is worried that development will happen in a patchwork way that doesn’t take into account environmental sustainability or quality of life for residents.

The government-appointed Lantau Development Advisory Committee has called for Lantau, Hong Kong’s largest island, to be developed into a tourism hub with seaside spa resorts and amusement parks. But this has been attacked as a ‘plunder of invaluable natural resources’ by citizen concern group Save Lantau Alliance.

Other plans have been floated to expand Tung Chung, a new town adjacent to the Hong Kong airport, and to develop the land around the Sunny Bay MTR stop, which connects to Hong Kong Disneyland and is currently surrounded by carparks and vacant lots. An even more ambitious proposal calls for the creation of a new artificial island off the coast of Lantau that would become a vast new development called the East Lantau Metropolis.

‘The main reason I live in Tung Chung is because of the green spaces, relatively quiet environment compared to Hong Kong Island or Kowloon and its proximity to the airport,’ says English teacher Derrick Chang, who’s lived in Tung Chung since 2014. He looks forward to new developments that will bring better restaurants and cheaper supermarkets to his neighbourhood, but hopes ‘it won’t cause too much traffic and foot congestion’.

That would be an ironic outcome for a project that succeeded in depositing Hong Kong’s millions of arriving visitors far away from Kowloon’s atmospheric but chaotic streets. But Lantau is huge – twice the size of Hong Kong Island – and half the area is country park. The days of aircraft landing between tower blocks and washing lines are long gone.

Hong Kong travel information

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English