Travellers seeking the new and modern among China’s metropolises might gravitate towards Shanghai. Beijing’s evolution, on the other hand, is more measured and subtle but no less thrilling – and definitely not to be ignored. We explore the fresh experiences and places that should be on your itinerary on your next trip to the capital.

1. The Mutianyu Great Wall by Helicopter

Fact: you can’t see the Great Wall from space. The best alternative? To see the Great Wall from a helicopter.

Mutianyu is already the most popular part of the Great Wall for overseas visitors and for good reason: it’s close, just 70 kilometres from Beijing; it’s far less touristy than overcrowded Badaling; and it’s more dramatic than the green-covered beauty of Simatai. And late last year, a new helicopter tour started to offer a whole new view of Mutianyu.

‘Seeing it from above really makes me wonder how they built it,’ says Snow Chen, a former pilot who founded G-Max helictoper tours. Chen started his company in 2015, flying over Badaling before expanding operations to Mutianyu. ‘People are now looking for more and more experiences,’ he says. ‘And with this, we can take you to the original great wall of Jiankou, where there’s no road and it’s not open to tourists. It’s a different perspective of the wall.’

Credit: View Stock / Getty Images

Immediately after takeoff, the Great Wall is difficult to spot, lost in the craggy peaks and scrubby landscape. But then it slowly comes into focus, winding and majestic. The scale of the wall is what is really striking. It snakes over peaks and continues on the other side; it collapses as if exhausted and then appears in the peripheries of your vision. This goes on and on. It seems endless.

The Four Seasons Beijing offers special helicopter trips over the Great Wall at Mutianyu. See fourseasons.com/beijing for more details

Credit: Imagenavi / Getty Images

2. Wangfujing

‘Wangfujing?’ you might be wondering. ‘The Wangfujing of deep-fried scorpions, hordes of flag-led tour groups and ageing chain outlets?’

Yes.

Indeed, over the past two decades, as Beijing glamour has shifted to the city’s east, this historic part of central Beijing, adjacent to the cultural tours de force of the Forbidden City, Tiananmen Square and the National Museum of China, has become a less and less desirable address. But hear me out: Wangfujing is changing.

3. WF Central

Let’s start with WF Central, the glamorous new complex sitting at the southern end of the capital’s oldest pedestrian street. This shiny hub of high-end shopping, restaurants, bars and a forthcoming 73-room Mandarin Oriental hotel opened in May – with big ambitions.

‘We want to try to improve the whole district. We’re hoping we can be the pebble in a pond and, from that, we can get a ripple effect,’ says Raymond Chow, executive director of Hongkong Land, the owner of WF Central and Hong Kong’s Landmark. ‘In 10 years’ time, I see Wangfujing Street becoming one of the most important international streets in the world. Everyone who comes to Beijing will have to come here at least once.’

Credit: Gilles Sabrie

4. Serpentine Pavilion

But it’s not just shopping, eating and indulgence; the district rides on its cultural and artistic heritage, a concept that has been infused into WF Central. On one side of the complex lies one of the hub’s biggest statements: the Serpentine Pavilion, a temporary space commissioned by London’s Serpentine Galleries. Designed by revered Chinese architect Liu Jiakun, the sculptural venue is the first Serpentine Pavilion outside of the UK and is arresting in its modernity, with steel beams arching across open space.

Until 31 October, the pavilion will host a programme of music, performances and discussions. ‘We want it to be a real hub, a real centre of energy, similar to what we do in London but very localised,’ says Hans Ulrich Oblast, artistic director of Serpentine Galleries. ‘We’ve worked extensively with local partners to have a shared vision for this special site. The pavilion is a content machine, not an empty shell. It’s very much a place for experimentation.’

Credit: Ole Scheeren © Buro-OS

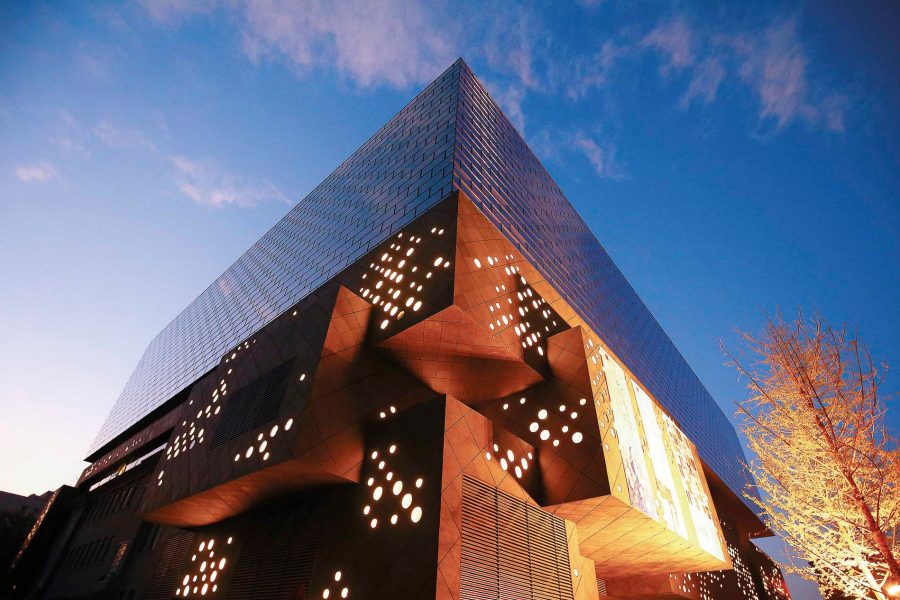

5. Guardian Art Center

Venture north, past the austere buildings of the past, and you’ll come across the avant-garde Guardian Art Center, which opened in October last year. The angular centre is the new headquarters of China Guardian auction house. And with 600,000 square feet of space, the group is branching out of the auction realm – and its own comfort zone.

‘Guardian is really well known for antiques. But that’s not all we do,’ says Wang Duan, one of Guardian Art Center’s curators. ‘With this centre, we want to do contemporary art too and put new things in front of the audience. Wangfujing is a very traditional area but we want people to learn about contemporary art, visit our programmes, get close to the art and talk to artists. We want this to be a new cultural landmark.’

There are big ambitions for the centre, with public exhibitions showing constantly and festivals. It’s all part of the changing face of Wangfujing. ‘The area is definitely changing,’ says Wang. ‘Soon, I think it will become much more elegant. Things are starting to move to Wangfujing instead of places like Sanlitun.’

Credit: Gilles Sabrie

6. Yan Jin Tang restaurant

In Xiaoyou Hutong, just north of Houhai Lake, down a couple of alleys, there’s an immaculate courtyard house. There’s no signage and pretty much nothing to tell you that this is one of the hottest restaurants in town.

Restaurant perhaps isn’t the best description of Yan Jin Tang (‘banquet hall’). It’s more of a private kitchen. Or, as chef Zhang Zhicheng calls it, ‘a place to eat’. One that has a two-month waiting list.

Credit: Gilles Sabrie

Zhang is something of a phenome. He’s only 24, opened Yan Jin Tang in July last year and is rather media shy. Yet, with his fine dining iteration of home cooking, he’s already being identified as the emerging star of Beijing’s food scene.

A lot of that has to do with his approach to hospitality. He serves every dish at the table personally, with a generous side of colourful explanation. He limits the space to 18 diners each night. And, most importantly to him, he’s willing to challenge the direction of modern Chinese food culture. ‘I see myself as a humble server and in that sense my approach harkens back to the traditions of the imperial court,’ says Zhang, whose nickname is Chubby. ‘People concentrate too much on presentation. For me, it’s about the food. But I also want to question the ideas around Chinese food. For example, there are many ways to cook a fish, not just steamed. The end result is all that is important to me.’

Credit: Gilles Sabrie

At Yan Jin Tang, he serves high-end dishes such as crawfish pickled with yellow wine; fish maw tempura with huadiao; and bird’s nest with orange. And Zhang hopes to open another spot soon to apply his philosophy to the staples of Beijing cuisine.

Credit: Chiara Ye

7. Equis bar

Beijing bars and nightlife have been dominated by two cliches: the mega club and the hipster hutong bar. Equis is both, and then some. It has a club with bands and DJs. It also has an intimate cocktail lounge called the Library. There’s a seafood bar, a members’ area and four sprawling terraces. Around every turn, there’s a different concept – which is kind of the inspiration. ‘The whole thing is designed around hutong style,’ says Keith Motsi, Equis’ head bartender. There are moutai cocktails here, as well as one of Motsi’s creations, a smoky Old Fashioned inspired by Beijing’s famous air quality.

With its unrivalled 80,000 square feet of space and its location in the growing business and consulate district of Liangmaqiao, Equis may just be helping to redefine Beijing’s entertainment scene. This isn’t the Gulou hutongs or Sanlitun, yet somehow it’s the hottest high-end bar in a very big town.

Hero image: Guardian Art Center by Ole Scheeren © Buro-OS

Beijing travel information

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English