Rain off the plane: how our pilots fly through bad weather

Flying through inclement weather is no fun for anyone. Turbulence in the cabin and extra pressure in the cockpit mean that storms are always best avoided. Pilots will endeavour to plot their way around bad weather: a mission that’s been assisted greatly by technology.

In the past, the briefing process for flight crew included paper weather maps showing the flight path, with drawn swirly clouds designating potential areas of bumpy weather. However, weather is dynamic, and a storm cell can develop and dissolve in an hour. That’s why charts showing weather eight hours out, for example, are an indicative guide, but conditions are likely to be different by the time the aircraft gets there.

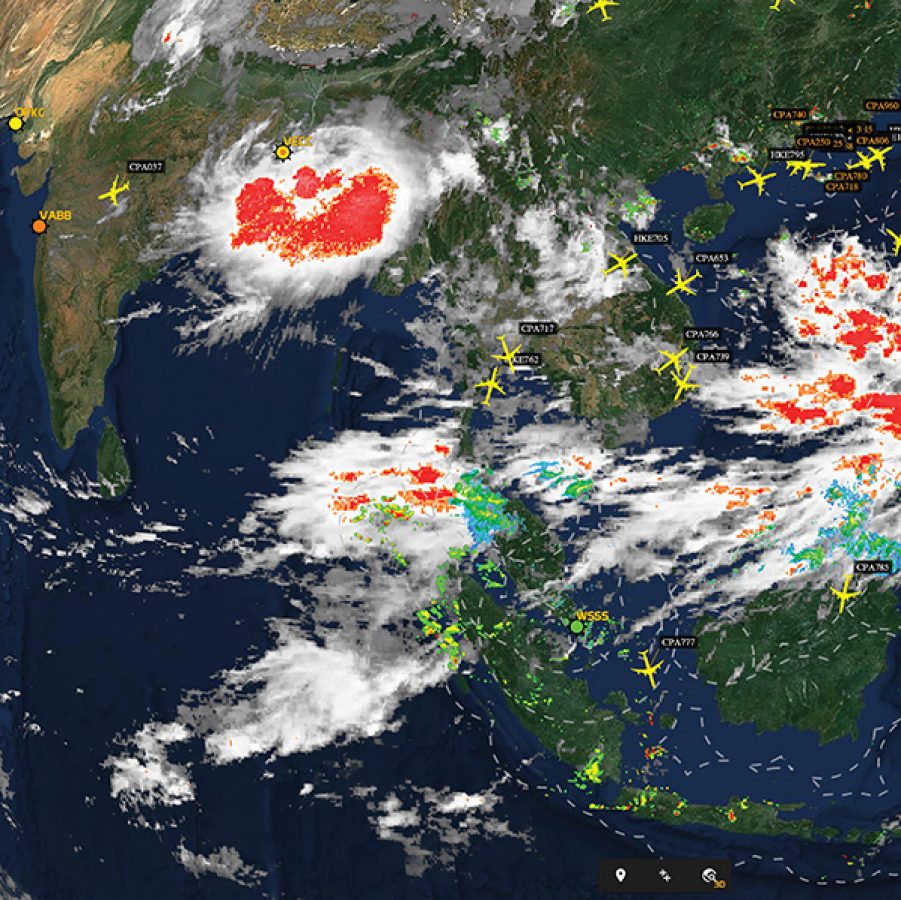

Nowadays, there’s a huge amount of live and forecast meteorological data available: from ground radar stations and satellites that they can read from their iPads to the weather radar on the flight deck, Cathay Pacific pilots have the best tech. Each has its limitations but, once they’re layered together, they give pilots access to information that pioneer aviators could only dream of.

Ground weather radar stations fire a beam of radio waves into the skies. The beam reflects off water droplets, and this feedback is converted into a colour gradient running from nothing to green through yellow, red and magenta, representing increasingly heavy droplet density and powerful convection: these are areas to avoid.

Of course, ground stations are land-based with a limited range, and many flights are oceanic. So another alternative comes from weather satellites, which also help with strategic planning. This data clearly shows cloud and weather systems but only from a top-down view of the globe, meaning that the satellites can’t see lower-level weather.

However, they do measure the temperature of the tops of clouds and mark in red areas of very low temperature. “These indicate the top of strong storm cells, which can reach 50,000 feet in height,” explains Head of Line Operations Captain James Toye. “The water droplets that are forced up that high by convection freeze, so the red areas indicate probable storm cells.”

If pilots need a more complete picture, they can also overlay live lightning strikes anywhere in the world, again from satellite data. “Lightning only happens in big cells,” says Line Operations Manager Captain Tony Pringle. “So even if you don’t have a great weather radar picture, you can still see areas where there is convective activity.”

For tactical adjustments once the flight is underway, pilots can use the onboard radar, which provides colour gradients indicating bad weather. With a clearest radar range of 80 miles on a Boeing 777 advancing at nine miles a minute, “you’ve almost got to start manoeuvring at once”, says Captain Toye.

Pilots will give storm cells a berth of about 20 miles to avoid their turbulent wake. If they know they’re approaching a large weather system, they’ll make sure they’re using every tool at their disposal to get the bigger picture. That way spirits are kept high in the cabin – and level in your glass.

More inspiration

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English

.renditionimage.450.450.jpg)