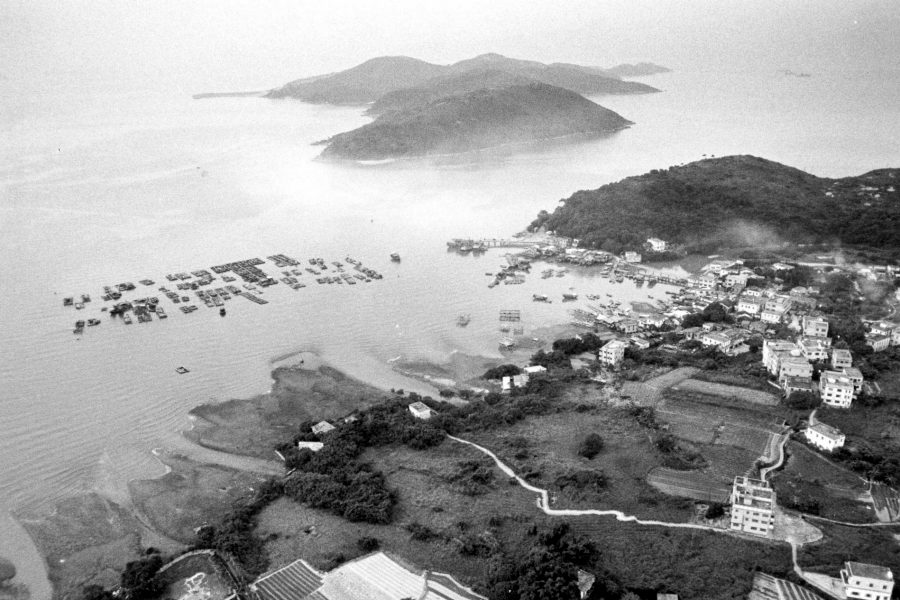

If you’re a time traveller in Hong Kong, you’d better pack a lifejacket because chances are the land you’re standing on wasn’t there 100 years ago. Since its first days as a city, Hong Kong has been shaped and reshaped by land reclamation, which has been an indispensable tool in turning 733 kilometres of craggy shoreline into a global metropolis of 7.5 million people.

Land reclamation is actually a bit of a misnomer; land creation would be more accurate. Mountains are levelled, holes excavated and the resulting soil and debris piled into the sea to extend shorelines or create artificial islands. Most of Hong Kong has been so thoroughly transformed through this process that, for many people, the city they remember from their youth no longer exists.

‘When I was small, I used to go to a friend’s flat to watch the dragon boat races,’ recalls journalist Chan Yuen-ying. ‘It was in a building on Gloucester Road in Wan Chai – which was the harbourfront then.’ That was in the 1950s. Today, it would be hard to see the harbour from the same spot, blocked as it is by the Convention and Exhibition Centre, Central Plaza and a thicket of skyscrapers.

‘I miss the sea,’ says Christopher Leung, who grew up in the Yau Ma Tei enclave known as Ferry Point. When it was first developed in the 1970s, it jutted out into Victoria Harbour. That changed when Hong Kong’s largest land reclamation project shifted the shoreline by nearly 600 metres to the west. ‘I would go downstairs, just a few steps and I was at the water. Now I can hardly see it.’

It’s still possible to trace the original waterfront in many parts of Hong Kong. In Wan Chai, Central and Sheung Wan, the twists and turns of Queen’s Road mark the spot where waves once lapped against the shore. Almost as soon as the British arrived in 1841, they began to push the shoreline outwards until it reached present-day Des Voeux Road in 1857.

The next stage of land reclamation was the young city’s most ambitious to date. Indian-born Armenian businessman Catchick Paul Chater hatched a plan to reclaim 24 hectares of land in the middle of Central. When work finished around 1900, the new land became the city’s most prized real estate, providing space for the Hong Kong Club, Supreme Court and Statue Square.

Over the next century, reclamation made room for airports at Kai Tak and Chek Lap Kok, along with business districts, container ports, factory zones and vast housing estates. But a turning point came in the 1990s, when 340 hectares of land were reclaimed off the west coast of Kowloon to make way for new roads, MTR lines and eventual mega-projects like the Express Rail and West Kowloon Cultural District. Just as that project was being completed, plans were underway to fill in the harbourfront from Central to Causeway Bay. The idea of filling in the whole of Kowloon Bay was floated.

People genuinely worried the harbour would one day disappear, which sparked a backlash that’s still felt today. In 1996, activist Winston Chu teamed up with legislator Christine Loh to pass the Protection of the Harbour Ordinance, which bans any future reclamation in Victoria Harbour unless there is an overriding public need. The reclamation for the newly opened Central-Wan Chai bypass was approved just before the ordinance was passed.

But reclamation is not off-limits outside the harbour. Government officials have proposed filling in parts of Tolo Harbour and Lung Kwu Tan to create more space for housing, and Chief Executive Carrie Lam recently unveiled plans for a massive artificial island that may be built off the tranquil south shore of Lantau Island. In Hong Kong, the ground under your feet is never quite as firm as it might seem.

1. Chek Lap Kok

About 900 hectares of reclaimed land tripled the size of the island for the new airport in 1998. The upcoming third runway will add a further 650 hectares.

2. Central

Waves lapped Des Voeux Road in the 1880s. Today, the new Central-Wan Chai bypass is the latest reclamation project to alter the shape of the harbourfront.

3. Kowloon

In 1900, Tsim Sha Tsui’s Clock Tower jutted into the sea. That changed in the 2000s when 340 hectares of land were added to the peninsula between Yau Ma Tei and Lai Chi Kok.

Hero image: SCMP

Hong Kong travel information

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English