Sometime in 2008, with very little fuss, a much-loved Sloane Street institution called The General Trading Company, or GTC, slipped quietly beneath the waves. It took with it a London indelibly associated with the young Diana Spencer, before and during the early years of her marriage to Prince Charles, and with it a 1980s cultural phenomenon known as the Sloane Ranger.

Today, Sloane Street is a narrow road that runs like a spine from the residential and retail quartier of Knightsbridge south to the almost-as-expensive but more villagey Chelsea and its main shopping drag, the King’s Road.

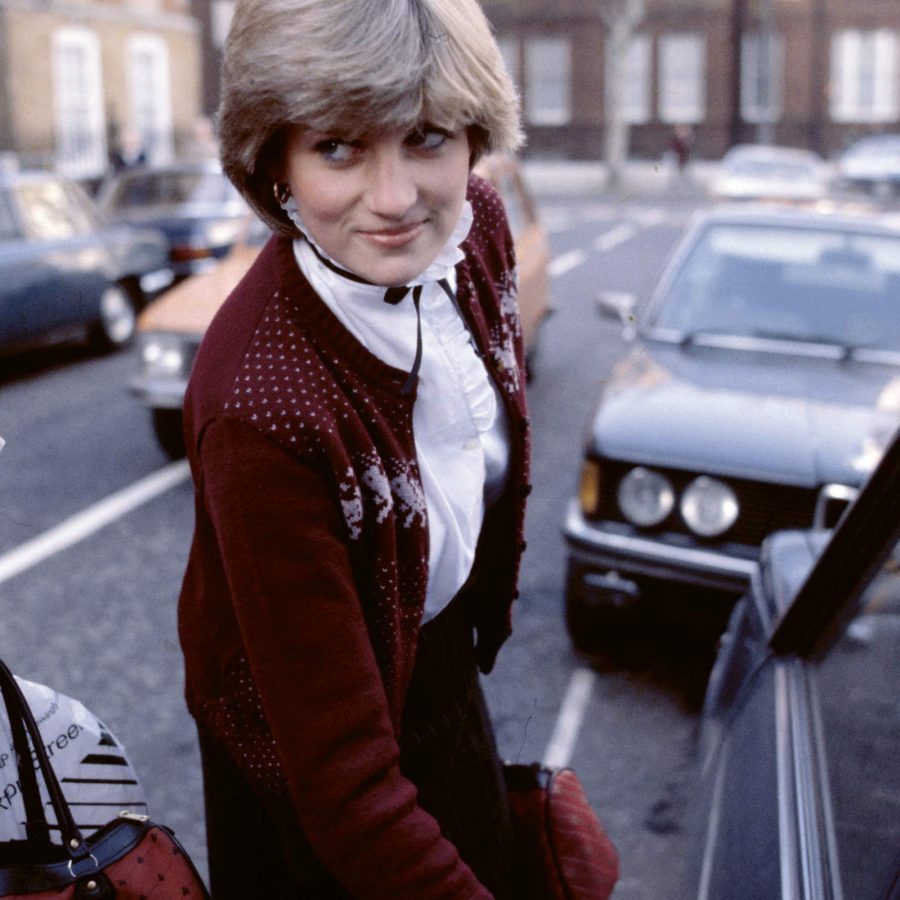

In Diana’s day it was the epicentre of an area of southwest London patrolled by young women in frilly collars, velvet knickerbockers and strings of inherited pearls. Fresh-faced men wore country clothing their grandfathers might – and probably did – own: baggy corduroy trousers in shades of toffee, brogues, V-neck pastel sweaters over checked shirts, short back-and-sides hair and, alarmingly, no deodorant.

They had their wedding lists at the utterly sensible Peter Jones on Sloane Square or, if their friends were richer, at GTC, which was wildly exotic by comparison: an emporium of Oriental (never ‘Asian’ or ‘Middle Eastern’) influenced goods, from kilims (carpets) to silk cushions.

‘Sloanes’, as they were nicknamed – occasionally affectionately, usually derisively – were broadly in the upper quartile of English society and Diana was their patron saint, being a genuine aristocrat, pretty and ultra-English. She was demurely, even frumpily, dressed until she reached her soignée maturity. The Sloanes’ only foreign equivalent (sort of) was the preppy style of their counterparts in the US.

Sloanes watched Brideshead Revisited, listened to Duran Duran and bought taffeta ball dresses from Tatters (for the rich) and Bellville Sassoon (for the very rich). The apogee was Diana’s vast, rumpled wedding dress, made by Elizabeth and David Emanuel – the former still has a shop in Mayfair.

The bible was The Official Sloane Ranger Handbook (1982), written by Peter York, who is still a social arbiter, and the late Ann Barr. I have a copy on my desk and it’s only now, with the 20th anniversary of Diana’s death, that I realise how young and how pensive she looks on the cover, in her off-the-shoulder frills, feathered bob and multi-strand pearl choker – and how utterly the London that she knew has changed.

For a start, ‘central London’ has doubled in size. The Sloane universe was Clapham, Fulham or Pimlico for first flats, Chelsea or Knightsbridge if you were lucky after marriage, and the City for work. The world their children live in, beyond Tower Bridge in the now-pricey East End, was terra incognita. Islington was odd. Today’s hot neighbourhoods – New Cross and Peckham in the southeast – were known, if at all, for crime. Brixton to them meant race riots.

And where are the Sloane Rangers themselves? Peter York wrote recently in Prospect magazine: ‘By 2000, London was becoming the first international city of the global super-rich. Since then, London’s prime and “super-prime” property – particularly the best, biggest houses and flats in Knightsbridge, Belgravia, Mayfair and the top slice of Chelsea – were bought out by an extraordinary mixture of Russian oligarchs, Middle Easterners, new petrodollar types from Nigeria, Indians, Malaysians and, latterly, Chinese…People with hundreds of millions. People with billions. Driving up the prices of London property and driving all but the richest, most adaptable Sloanes further south and north – and some out of London altogether.’

I’ve been walking the streets of Diana’s London to see what’s left – and what has, like the Sloane Rangers, gone forever.

Sloane Square and the King’s Road

One of London’s finest mismatches is the Royal Court Theatre (iconoclastic since opening in 1956) facing Peter Jones� (the Mr Sensible of the retail world) across Sloane Square.

But they’ve both changed. Start at PJ’s excellent rooftop café, with views over the chimney pots and roof gardens of Knightsbridge, then trawl the King’s Road, detouring into Duke of York Square – a military barracks in Diana’s time, now a shopping enclave – and, for old times’ sake, The Pheasantry, former trendy bar/restaurant, now a Pizza Express Live jazz venue and supper club.

The Made in Chelsea set film at Raffles, a nightclub back in my day, but I prefer old pub haunts such as The Phene and the revamped Cross Keys, off the King’s Road. Hop on the 19 bus back to Sloane Square and up Sloane Street to see Harvey Nichols, the store sprinkled with Diana-dust in the ’80s, now with buzzy Fifth Floor food hall, bars and restaurant. Finish with a drink in the bar beneath the Royal Court and move on to newly revamped The Botanist or Colbert to see neo-Sloanes tucking into ‘supper’.

South Kensington and the Fulham Road

Grubby South Ken tube would be barely recognisable with its pedestrianised apron of flower stalls and buskers. Try the V&A Café, the world’s first museum café, designed by William Morris, before strolling down to Brompton Cross for Chanel, 3.1 Phillip Lim and Stella McCartney. Tackle the jewellery-box boutiques on Walton Street: leather loafers or baby linen, anyone?

End with champagne and oysters at Bibendum, in the lavish 1911 Michelin Tyre headquarters which is also home to vintage Sloaney interiors boutique The Conran Shop, or The Enterprise on Walton Street. Pubs down the Fulham Road include the revamped Hollywood Arms and the Anglesea Arms with its packed sun terrace.

Live the ’80s

Buy retro gear – mohair sweaters with batwing sleeves, pedal pushers, New Romantic pirate shirts – from Rokit in Brick Lane, Covent Garden or Camden.

Have a pint at the ‘Sloaney Pony’, aka The White Horse pub in the Sloane heartland of Parsons Green, now with a dinky, bricked-off beer garden with umbrellas.

Throw a bash at a posh London venue such as Searcys at 30 Pavilion Road – there since the 1920s. Then book Juliana’s – the ‘travelling discotheque’ to have at one’s 18th or 21st – now a chic DJ outfit (you can book them in Hong Kong, too).

Dine at San Lorenzo, Diana’s regular and much-papped haunt on Beauchamp Place in Knightsbridge, but mix up the experience with a pre- or post-prandial stint at Layalina shisha lounge just up the road.

Kensington High Street and Kensington Gardens

Walk up Exhibition Road and across Hyde Park to Kensington Gardens, passing the Albert Memorial (Sloanes loved this elaborate monument to Queen Victoria’s deceased husband) and the Royal Albert Hall, which hosts everything from tennis to rock concerts and is famous for its summer concert series, the BBC Proms. Keep going west to Kensington Palace, home to Will and Kate, the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge; and Diana’s grandchildren, George and Charlotte. Young William and Harry lived there first with both parents and latterly their mother.

From the palace, take kids to the Diana, Princess of Wales, Memorial Playground, with its much-loved pirate ship, then to Notting Hill to visit Portobello Road Market (best on Friday or Saturday) and peek at the young princes’ first school, Wetherby Pre-Prepatory School, on Pembridge Square. Adults: south is Kensington High Street, top shopping plus classic drinks or dinner venue the Kensington Roof Gardens, fashionable ever since it opened in the ’80s.

The Week that Followed

For Londoners, the abiding memory of Diana’s death is the glistening meadow of cellophane-wrapped flowers outside the Augustan frontage of her home, Kensington Palace.

I went there as the meadow began to spring up. So many of those first mourners on 31 August 1997 were Arab women. They were wandering over on that hot late summer night from the ‘Little Beirut’ of Edgware Road and the smart apartment blocks of Knightsbridge. I recall there were as many remembrances and tears for the Egyptian boy, Dodi Fayed, as for his girlfriend, the Princess.

But in the days that followed, Britons flocked to the palace in their thousands to cry for Diana and add to that field of flowers.

It was the most surreal week I, and many other Londoners, ever lived through. The streets continued to bake in the unaccustomed September sun. People couldn’t work. I went for a walk and saw shirt-sleeved businessmen queuing for hours and hours to sign the books of condolence at St James’s Palace.

Those febrile days are captured in Stephen Frears’ superb film, The Queen. It’s been said since that Britain came closest to a revolution that week than at any time for the past 300 years. But in the end, we preferred to express our profoundest emotion in the most British way imaginable: by finding a queue and standing in it.

London travel information

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English