Everyone has had that moment on their travels: the pure, eye-opening, mind-altering delight that comes with tasting a delicious food for the first time. It’s visceral and cerebral. Your taste buds have learned something new. And you wonder how to recreate this food at home.

A few hundred years ago, the Japanese had this moment. When Portuguese missionaries crossed oceans to Nagasaki, they brought European cakes and sweets as a friendly gesture. At the time, Japan only used plant-based ingredients to make desserts; sugar was a luxury and not commonly used as an additive. When the Japanese who greeted the missionaries – famed shogun Oda Nobunaga among them – first tasted these European confections made with eggs, flour and sugar, well, it’s not difficult to imagine their reaction. An obsession was born.

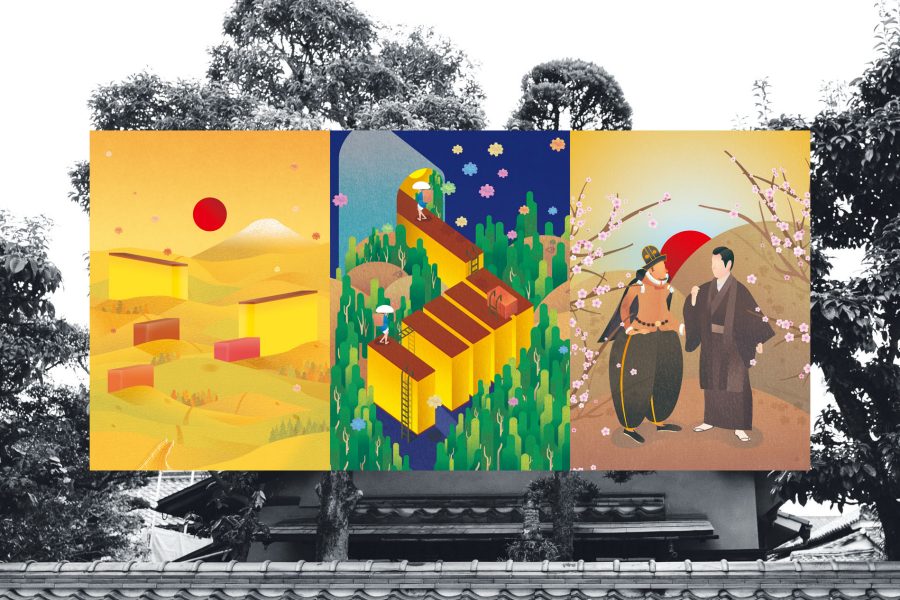

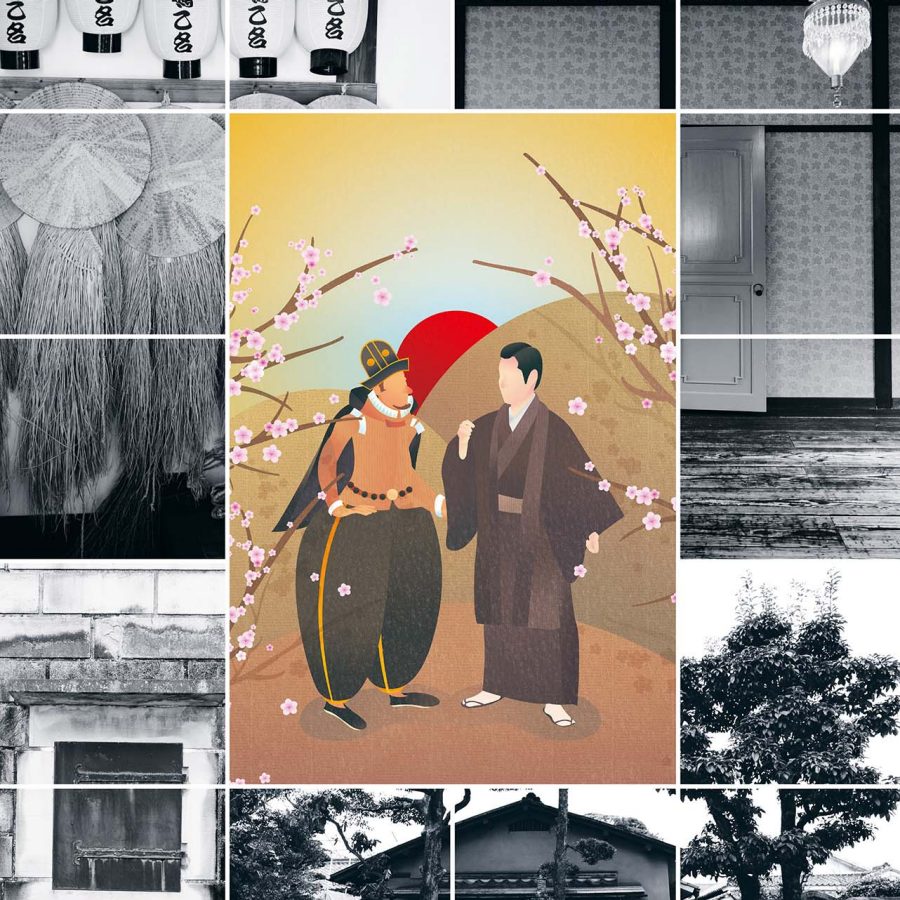

Illustrations: Cecil Tang; Photography: Prairie Stuart-Wolff

During the Edo era (1603-1867), not long after the missionaries’ arrival, Japan began a vibrant trade with the Portuguese and the Dutch. European goods, including sugar, started to arrive. They first passed through Nagasaki Kaido, a path cutting across Kyushu island, before being distributed throughout Japan. European-style desserts and sugar, now a growing commodity, became part of the Japanese palate, and the Japanese started to learn how to recreate these foods. Sugar was also used in Japanese snacks, starting a culture of what we recognise today as Japanese-style desserts. Nagasaki Kaido’s role in this history led to its nickname: the Sugar Road.

It’s an exciting prospect, to follow the Sugar Road – I have a sweet tooth after all. The road starts in Nagasaki in the west and ends in Kita-Kyushu City in the east, a journey spanning 228 kilometres, passing through three prefectures – Nagasaki, Saga and Fukuoka – with more than 20 ‘service areas’ (places to lodge and explore) along the way. Although the route has shifted over the centuries, and some parts no longer exist, the desserts and stories of each stop still provide a vivid, delicious glimpse into the past.

Illustrations: Cecil Tang; Photography: Prairie Stuart-Wolff

It all starts on Dejima, an island in Nagasaki, where two tidy rows of Edo structures seem to have been frozen in time. The shogunate designated the manmade island a place to house the Portuguese residents, and later the Dutch Trading Post warehouse complex was built there. It still stands today, with a sugar scale found at its entrance to commemorate this important Dutch commodity; for years this was where all sugar imports into Japan made landing. This complex of about a dozen wooden buildings has been rebuilt based on the original Dutch structures.

It’s not very large, but the site has everything a trading company outpost would need, including the captain’s residence, offices, warehouses and a kitchen. In 1759, during the height of the sugar trade, 1,375 tonnes of sugar was imported through this complex.

During the Isolationism period (1641-1859), the Dutch East India Company was Japan’s sole European trading partner. Japan also banned its own citizens from following Western religions – but the influence of Western culture persisted, at least when it came to food. In fact, it appears that food was a prominent facet of cultural exchange. The Dutch Trading Post showcased an elaborate Christmas feast, calling it a winter feast due to religious sensitivities.

The shogunate may have been determined to limit foreign influences on its people, but it couldn’t keep foreign foods from invading their taste buds. The Japanese started to learn to make European desserts on Dejima, absorbing these foods into the local culture. Castella cake, for instance, was initially brought by the Portuguese, developed through Dutch teachings, and became Nagasaki’s signature cake.

Illustrations: Cecil Tang; Photography: Prairie Stuart-Wolff

After Nagasaki city, I headed east to try the desserts intertwined with each historic service area. Still in Nagasaki prefecture, the city of Isahaya is known for its okoshi, a confection of puffed rice and sugar. Kashuen Moricho, a company that makes okoshi and castella cake, has been churning out desserts since 1793.

‘Large quantities of sugar was brought to Isahaya in the Edo period, and this area has very high-quality rice, factors that brought us to make these desserts,’ says Mori Atsushi, Kashuen Moricho’s seventh generation proprietor.

Leaving Nagasaki prefecture, I came to Saga prefecture’s Ogi City service area. It’s an idyllic town of hills and streams, a place called Little Kyoto for its beauty. Muraoka Sohonpo, a shop that makes yokan (sweet bean paste jelly), is found here. With his deep knowledge of Japanese desserts, owner Muraoka Yasuhiro even opened a yokan museum in the shop’s sugar warehouse. People started to forgo the pueraria plant in favour of sugar to make yokan starting in the Edo period, he tells me. The yokan from this area have a layer of crystallised sugar on the surface, giving it a slight crunch on the outside. Saga also has a speciality sweet called marubouro, which was derived from Portugal’s round bolo cake. Wheat, an important bolo cake ingredient, is a major local product, which has contributed to the dessert’s production.

Tasting my way into the Sugar Road’s history may sound romantic, but there’s a certain abstraction in connecting modern food to the past. So when I heard about a section of the road that’s retained much of its old look, I had to make my way there. That’s Yanagi-machi, which in the Meiji era (1868-1912) grew into a major trade centre filled with banks and merchant homes. This area has undergone intense restoration in recent years, reviving Western-style red-brick houses as well as Japanese architecture of white walls and grey tile roofs. Amid the old buildings, many tourists like to enhance the historic effect by donning kimonos from surrounding shops.

By the Meiji period, Japan had begun producing its own sugar, and in great quantities. It had also gained hundreds of years of experience making European-style desserts. It was near the end of the Sugar Road, in Fukuoka prefecture’s Iizuka City, that I really got a taste of the marriage of the two cultures, thanks to a baked bun called chidori manju. Marubouro is used to make the crust, and the filling is bean paste, a very Japanese ingredient.

Illustrations: Cecil Tang; Photography: Prairie Stuart-Wolff

‘For 300 years we’ve been making castella cake and marubouro, and in 1927 we started combining the two to make chidori manju,’ said Harada Mikinori, owner of Chidoriyahonke, which first created the hybrid bun. ‘Through today’s desserts, we can see how the Sugar Road accelerated the exchange between Western and Japanese cultures.’

At the end of the Sugar Road, at coastal town Kita-Kyushu City, the scenery seems to switch from the Edo period to modern day. Back in the day, goods were moved through the narrow Kanmon Straight to Honshu, Japan’s largest island. Here, Irie Confectioner is working hard to revive Portuguese konpeito, the colourful candy that comes in small, bumpy spheres. Much beloved by the shogun Oda Nobunaga, konpeito has lost popularity over the years. ‘There are fewer than 10 shops making konpeito in Japan, and we’re working to renew this item in its taste and in its packaging,’ says Irie Masahiko, the company’s owner.

Tokiwa Bridge was the journey’s final stop, and this is also where the Sugar Road ends. But it marks the beginning for the rest of Japan’s sweet obsession.

On the sugar road

JR Kyushu Sweet Train Aru Ressha

Passengers on this antique train enjoy bento boxes and various desserts created by famed chef Yoshihiro Narisawa. There are two routes, one of them going from Nagasaki to Sasebo, passing by scenic Omura Bay.

Glover Garden

This garden is located in the 19th-century area of Nagasaki that was formerly set aside for overseas residents and surrounded by many other mansions and facilities built by British traders. The Former Glover House is Japan’s oldest Western-style wooden building, completed in 1873.

Chou Chou Farm

Perched on the edge of Omura Bay, this farm holds dessert and pastry workshops that use freshly picked fruits as ingredients. Fruit-picking activities are also on offer.

Ureshino Onsen

Ureshino was a service area along the Sugar Road during the Edo period. It’s home to one of Japan’s top three onsens known for beautifying effects. Speciality foods include tofu cooked in hot springs and Ureshino tea.

Saga Balloon Museum

Saga plays host to the annual Hot Air Balloon World Championship in November. The museum boasts a remarkable archive and interesting information about hot air balloons. Visitors can also try Japan’s only hot air balloon simulation machine.

Hero image: Illustrations: Cecil Tang; Photography: Prairie Stuart-Wolff

More inspiration

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English