The story of urban planning in Singapore starts more than 50 years ago. On 12 September 1965, shortly after Singapore had been cast out of the recently formed Malayan federation and had subsequently declared its own independence, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew stood before a crowd of town hall supporters and said, ‘We made this country from nothing, from mudflats! Ten years from now, this will be a metropolis. Never fear!’

By any yardstick, this was a bold, even hubristic prediction to make. Granted, 150 years of British colonial rule had created a thriving entrepôt based around the port, a well-oiled civil service and a rather picturesque skyline of neoclassical and art deco piles clustered around the southern tip of the island. But outside the central business district were mudflats and swamps, and dirt-poor kampong villages. Most of the population lived in squalid, crowded tenements. There was no reliable water supply. In real terms, the average Singaporean in 1959 was as poor as the average American in 1860.

Against this sobering background – a metropolis in a decade? But as history shows, Lee’s bold prediction came true. And then some.

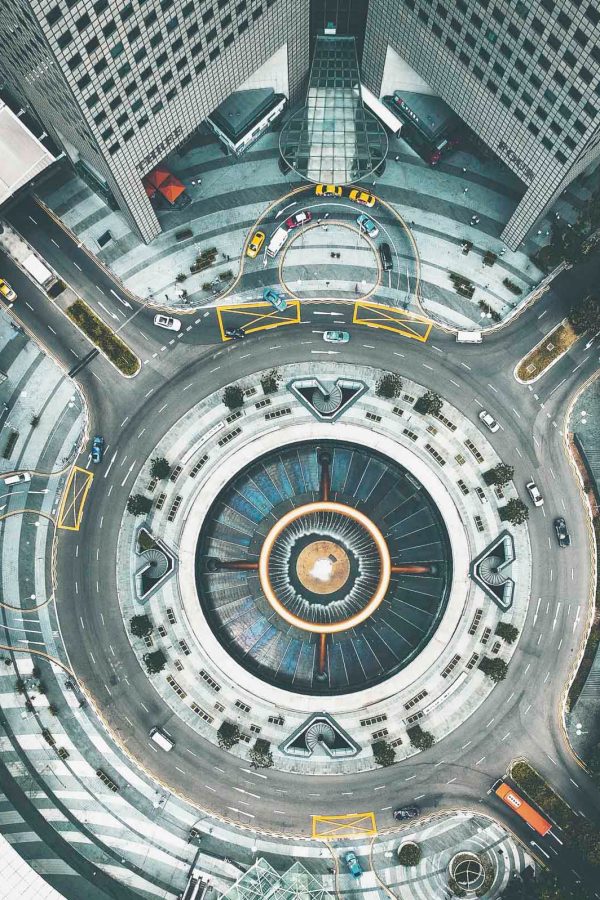

Credit: Idroneman

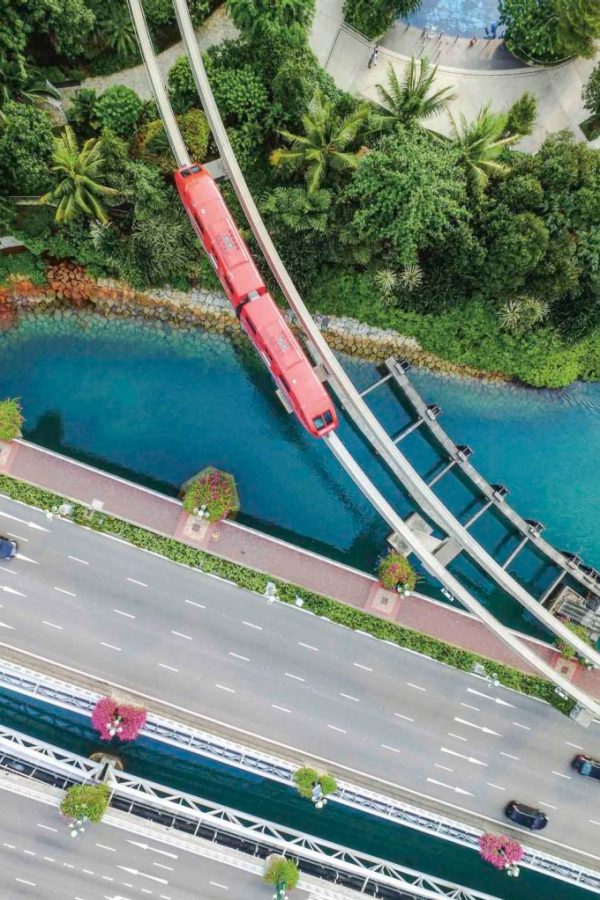

Credit: Idroneman

Today, the urban planning in Singapore has created a gleaming city of the future, a global financial centre. Framed by lush, leafy greenery at every turn, its skyline features a dizzying collection of designs by the likes of IM Pei, Kenzo Tange, Paul Rudolf, Zaha Hadid, Ole Scheeren, Norman Foster, Richard Meier and Moshe Safdie. Its public infrastructure – comprising a comprehensive transportation network, education system and superb roads – serves a population of about 5.8 million in a landmass that clocks in at barely 720 square kilometres.

Singapore got here via long-term planning. Its small size and confinement as an island mean every square metre matters. The broad planning principles include building mostly high-rises to save space, carefully considering the balance of buildings’ functions, incorporating plenty of greenery, strategically developing towns outside the CBD, creating more land through reclamation and, critically, ensuring enough housing.

Over 90 percent of Singaporeans and permanent residents own their homes – a remarkable accomplishment that owes much to Lee’s conviction that the surest way to create a sense of identity and to accumulate wealth was to give Singaporeans homes of their own. Home ownership, he believed, grounded people, and made them stay and work and build families and links to the community.

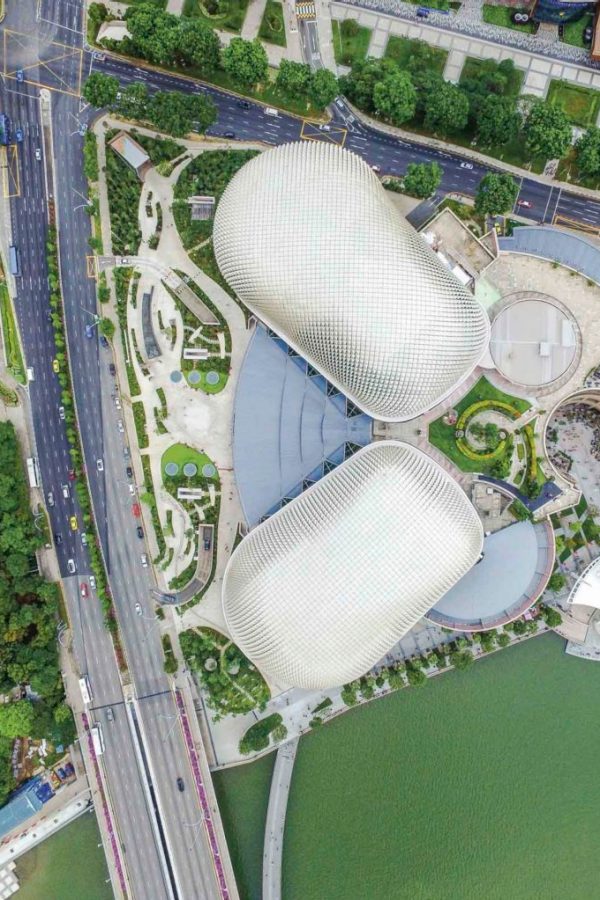

Credit: Offstone/Getty Images

‘By 1985, we had all the necessary infrastructure in place,’ says Liu Thai Ker, chairman of the Centre for Liveable Cities’ advisory board, who credits the successful urban planning in Singapore to political leadership and stability.

‘We had broken the backbone of the housing shortage with affordable, subsidised public housing. The first phase of the underground trains was underway. We were ahead of the times in worrying about global warming when we introduced building standards that minimised the amount of heat absorbed. We emphasised greenery in public spaces, especially along our roads. It was all planned, even our pavements and the covered walkways around public buildings.’

At the 2010 Venice Architecture Biennale, the Singapore Pavilion, 1000 Singapores: A Model of a Compact City, made waves for its astonishing conclusion that by using its urban planning model, a thousand Singapores – roughly 0.5 percent of the Earth’s landmass, or an area the size of Texas – could comfortably hold the world’s population.

Credit: Marcus Mok/Getty Images

Credit: Idroneman

Singapore’s smooth traffic, comprehensive infrastructure and general ease of living are hard to argue against. But at the same time, its model of high-density living, albeit one punctured by vast interior swathes of secondary-growth jungle, is not to everyone’s tastes. Critics say it’s an artificial construct devoid of spontaneous, organic growth; that the emphasis on a controlled urban plan has resulted in a sterile city. In the 1990s Lee also acknowledged the mistakes of demolishing heritage buildings in the city’s early rush to rebuild.

But Peter Barrett, an urban designer who has lived in Singapore for over 20 years, says the criticisms ignore both history and context. ‘Every city needs to evolve and find its own way,’ he insists. ‘In the beginning, Singapore was coming out of a turbulent independence period from Malaya. It needed to carefully control its resources, including land development. It had limited land. This is why sustainable and balanced development from a commercial and community point of view drove the government’s controlled land development.’

Richard Hassell, whose firm WOHA has worked on some of the city state’s most striking projects, is equally bullish about the model of urban planning in Singapore. ‘How can a city be perfect?’ he says. ‘Singapore has transformed at an unbelievable speed into a world city with an amazing quality of life. And it works superbly with continuous improvements and unceasing upgrades of infrastructure. Transport works, industry works, commercial areas work, and the planning authorities have a clear vision of a live-work-play vibrant city in a tropical garden, which is exactly what is being delivered. Singapore is really good at the big picture. Water, waste, sewerage – all these things are the best in the world.’

So much so that, these days, a steady stream of city planners and government officials from China, Southeast Asia, South America and Africa come calling on Singapore, where the Nanyang Technological University, the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy and the Centre for Liveable Cities offer practical courses taught by practitioners for overseas officials up to the mayoral level, including leadership courses in urban governance and planning.

To Liu, the successful story of urban planning in Singapore is about grit, hard work, inspired political leadership and an uncommon regard for the good of the greater community. ‘You want people to live in a good environment,’ he says. ‘But nothing you want to achieve in a city like Singapore happens by accident.’

Hero image: Mosaic of Singapore; Carlina Teteris / Getty Images , Gallerystock / Snappermedia, Gallerystock / Snappermedia, Idroneman

More inspiration

Singapore travel information

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English