Recounting the many miles and tall tales of Odoric of Pordenone

Had Friar Odoric of Pordenone submitted to a job interview in April 1318, before being despatched from Padua, Italy as a Franciscan missionary-cum-itinerant diplomat, here’s how he might have responded to that ticklish invitation: ‘Tell us about yourself’.

‘I’m 32, took my vows at Udine in northern Italy, and I’m just back from the Balkans and southern Russia where I had my work cut out preaching to the Mongols. Oh, and my father used to work for King Ottokar of Bohemia.’

But could he have provided an accurate response to that HR manager standby: ‘Where do you see yourself in five years’ time?’

In point of fact, the next dozen years saw the footloose friar trot haphazardly across the globe on a mission to put out diplomatic feelers; the previous century, Mongol hordes had laid waste to Poland and Hungary – some bridge-building was in order, and Odo was designated chief engineer.

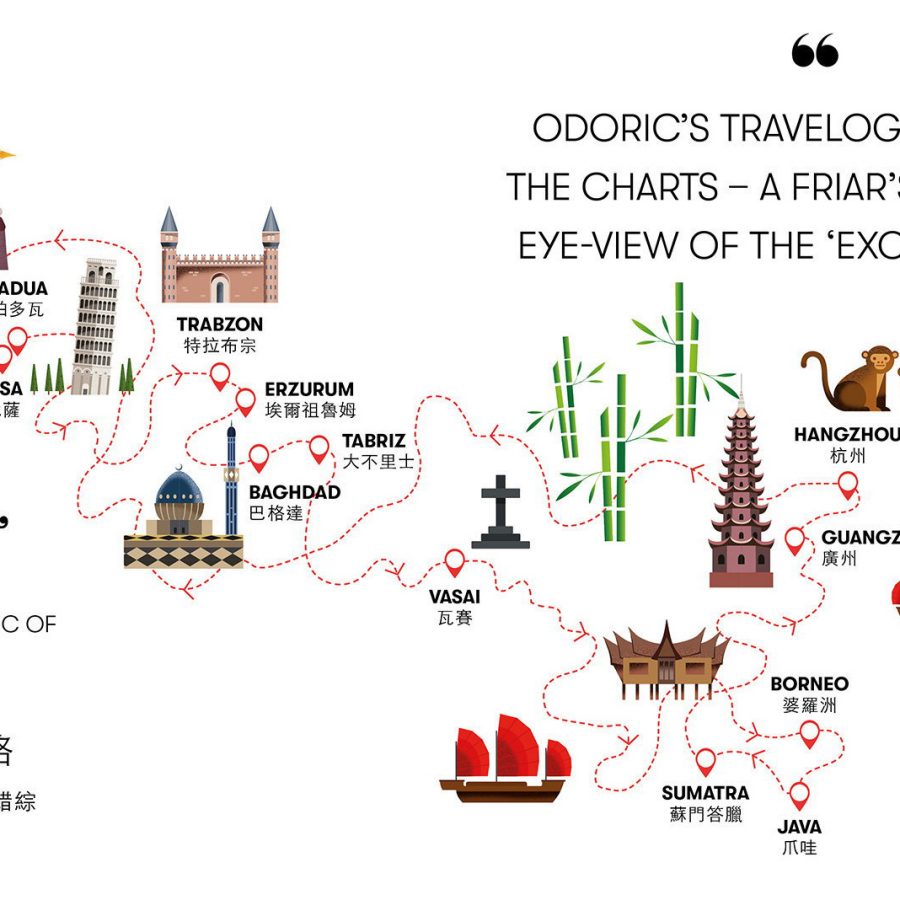

He began by crossing the Black Sea to Anatolia – dropping in on Franciscan houses in Trabzon and Erzurum (modern-day Turkey) – before preaching his way around the Middle East from Tabriz (Iran) to Baghdad (Iraq), and arriving on the west coast of India at Thane, near Mumbai. Here he picked up the remains of some martyred colleagues, which he happily lugged about the country on his travels, until he found a suitable resting place at a church near Vasai. He later set sail in a junk for Sumatra, via Java and Borneo, before arriving at the Chinese port of Guangzhou.

He didn’t travel alone. At least part of the way, he was accompanied by his BFF (Best Friar Forever), who went by the singular moniker of Brother James of Ireland. I can well understand the attraction of accompanying Odo: fresh horizons, a lust for adventure, a soupçon of fame, to be sure. I can just visualise the pair skipping from port to port, rolling eyes at unfamiliar menus and swapping puns in Latin.

Illustration: Lok Wong

Back home, he settled down to put everything he’d seen and done on parchment. He had the gift of pithy observation, noting the Chinese habit of growing fingernails long and the prevalence of nudity in Sumatra. He was gobsmacked by the concept of paper money. And anything to do with animals got several paragraphs. At a zoo in Hangzhou he witnessed thousands of monkeys summoned by gong at feeding time, and near the Black Sea observed ‘a certain man taking about with him more than 4,000 partridges gathered about him like chickens about a hen.’

But Odo’s reportage went beyond mere anecdotes: he could see that Asia had many valuable secrets to impart. Pepper, rhubarb, bamboo and sago – all new foodstuffs as far as he was concerned – caught his attention, as did the widespread use of herbal medicine. And he was no blinkered Eurocentric, freely admitting that China’s postal system was far superior to anything that existed in the West.

As far as was possible at a time of limited literacy, Odoric’s travelogue topped the charts – a friar’s must-read eye-view of the ‘exotic Orient’. Contemporary authors plagiarised his text shamelessly, though later critics have raised eyebrows at some of his fanciful tales.

Friar Odoric died near Pisa in 1331 with a full-scale funeral organised. What happened to Brother James, history does not relate: but I like to think of him keeping fellow drinkers spellbound with tales of his riproaring adventures alongside Odoric in some rural shebeen: ‘Honest now, around Canton they train these black birds to catch fish…’

Mileage Run: Odoric vs Today’s Traveller

Route

Odoric: Pordenone, Italy – Hangzhou, China (return)

You: Milan, Italy – Hangzhou, China via Hong Kong (one-way)

Duration

Odoric: Around 12 years

You: 15 hours, 15 minutes

Stopovers

Odoric: At least 40

You: Just one

Asia Miles (Economy)

Odoric: 46,200

You: 14,600

Asia Miles Per Hour

Odoric: 0.44

You: 957

Entertainment

Odoric: Meeting cannibals, carrying martyr bones, visiting Maharajahs and Khans...

You: 1,000+ hours of inflight entertainment including movies, TV and music

Hero image: Getty Images

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English