Standing on ruler-straight Qianmen Street in the historic heart of Beijing, it feels like you’ve stumbled upon a themed cultural village. The paved stone road is so polished that it looks recently laid. Gleaming tram tracks run along the middle, shaded by a canopy of trees. On either side are rows of ornate Qing dynasty-style buildings, with grey brick facades and red pillars in such immaculate condition that they could be newly constructed.

Credit: Geng Kunpeng/Getty Images

Credit: Daifawel

Credit: DuKai photographer/Getty Images

Within those edifices are brightly lit shops and eateries – some dating back centuries – selling a smorgasbord of traditional Chinese snacks, teas, medicine, souvenirs and more. These include Bianyifang Roast Duck Restaurant, founded in the 15th century, Changchuntang, a pharmacy more than 200 years old, and Jin Fang, a Muslim sweet store that’s a mere century old. Around us, crowds of sightseers are snapping photos of this film set-like wonderland that was once the main commercial thoroughfare leading into the inner precinct of the former imperial city.

Our primary reason for coming here isn’t to eat or shop, however, but to get a sense of Beijing’s Central Axis, a masterpiece of Chinese imperial design and urban planning that was inscribed on the Unesco World Heritage List last year. Running from north to south, the axis encompasses a roll call of Beijing’s must-see sites and more than 700 years of history.

It begins in the north at the Drum and Bell Towers (built in the 13th century, with a morning bell and evening drum to help keep time) and extends 7.8km south to Yongdingmen gate and the World Heritage-listed, 15th-century Temple of Heaven, whose tiered and conical buildings were used for making sacrifices in return for bumper crops.

Credit: Yestock/Getty Images

Credit: Natalia Garidueva/Getty Images

Credit: Sanga Park/Getty Images

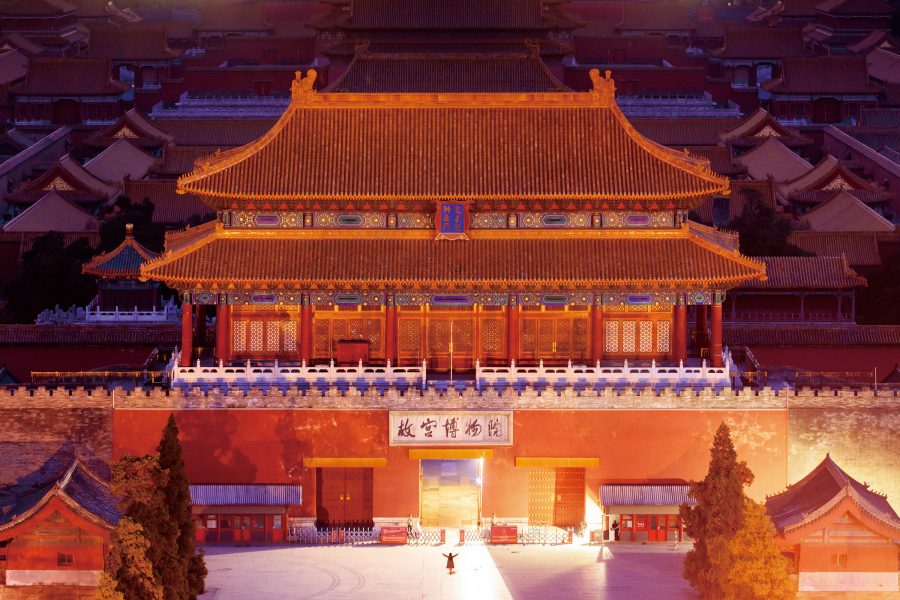

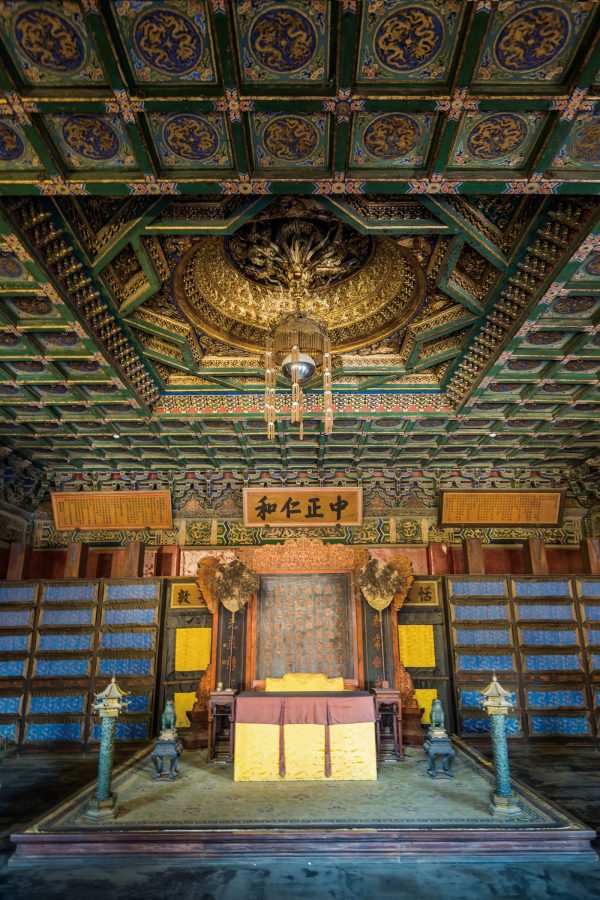

In between are Jingshan Park, a royal garden built from excavated soil dug from the moat of the Forbidden City (another World Heritage site, built in 1420 and home to the Palace Museum since 1925); Tiananmen Square, which has been significantly enlarged since it was established in the 17th century; Zhengyangmen, gateway to the historic centre; and other significant landmarks.

The axis is unusual in that it is a living, evolving heritage site; a palimpsest of dynasties and architectural styles that originated during the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368), with additions during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), Qing dynasty (1636-1912) and even today. It showcases Chinese imperial thought, one that emphasises how symmetry in urban planning leads to order and harmony in society. The axis includes imperial palaces, city gates, gardens and ceremonial temples alongside newer museums and public buildings, all observing the ideals of symmetry set by its architects.

Credit: Yestock/Getty Images

Credit: Jon Hicks/Getty Images

Credit: Yestock/Getty Images

Many of the ideas are derived from the Kaogongji, which has variously been translated as the Book of Diverse Crafts and Records on the Examination of Craftsmanship, among other titles. It’s the world’s oldest known technical encyclopaedia, dating back to 300 BCE and covering subjects including chemistry, technology and urban planning. In scale, proportion and continuity of design, the axis is unique globally, while still influencing the planning of other capital cities in Asia.

Depending on your energy levels, you can explore the axis on foot or by bicycle or car. We opt for a cycling tour, which offers a mix of mobility and flexibility, allowing us to cover a good portion of the axis while being able to get on and off as we like.

Setting off from the Mandarin Oriental Qianmen, Beijing , a new hotel in the historic Caochang hutong located within the perimeter of the axis, we cycle through atmospheric laneways where locals reside in traditional siheyuan, or courtyard houses. All of the hotel’s 42 gorgeously restored rooms are in these individual courtyard houses scattered around the hutong, making for a truly immersive experience. Staying here, it’s easier to comprehend that the axis isn’t just famous monuments, and that it influenced, and continues to influence, the way people live, with hutongs following similar linear orientations.

We cut through Sanlihe Park, where willow tree branches droop into babbling brooks. The park is reminiscent of the water towns of Jiangnan, only smaller and less touristy. It’s hard to believe that this oasis of tranquillity is at the centre of one of the world’s largest and busiest cities, with the park exit just moments from the bustle of Qianmen Street. From here, near the midpoint of the axis, the visual cues are easy to pick up.

Credit: Twenty47studio/Getty Images

Credit: Elena Odareeva/Getty Images

Directly in front of us is Zhengyangmen, behind it Tiananmen Square and behind it, farther, the magnificent Forbidden City. These are sites we’d treated as individual attractions on previous trips to the capital. Now, with Beijing’s Central Axis elevated to World Heritage status, we’re able to recognise that each landmark equals a sum greater than its parts; an ingenious grand plan that has not only survived through the centuries, but adapts and thrives amid the continued march of time.