Nick Tsao redefines the ancient art of papercutting

Folding a square of paper, snipping away at its edges and then opening it out to reveal an intricate lantern or a unique snowflake. For most, it’s a memory of childhood. For Hong Kong architect and artist Nick Tsao , it’s a way of life.

What started as more of an experimental pastime for the Cambridge-trained architect has become a full-time pursuit. He welcomes us into his flat at the Blue House heritage building in Wan Chai, which is also home to his design studio, Papertecture . Here, he lives, works on his art and hosts workshops teaching others his craft.

“The beauty of papercutting lies in its vast creative potential and immediate gratification,” Tsao says. Papercutting is one of the oldest Chinese folk arts, dating back some two millennia. It’s long been a popular, cost-effective way to decorate the home, especially during festivals such as Chinese New Year, when red paper art brings in luck and happiness.

His foray into this historic folk art was born of frustration. “One Chinese New Year, I searched the markets for papercuts, but found only stiff, traditional or cartoonish designs.” Tsao created his own, honouring tradition by using red paper and Chinese zodiac themes but, in a creative twist, swapping stylised imagery for more realistic depictions and incorporating a touch of humour and fun.

“The beauty of papercutting lies in its vast creative potential and immediate gratification”

Years of making architectural models had primed him to think about paper in a sculptural way and trained him to observe nuances in his environment. His designs range from the traditional, like dragons or auspicious fai chun decorations to modern, complex images such as an origami handbag for Dior or the human musculoskeletal system in miniature, created for a talk on osteopathy.

Credit: Elvis Chung

Blueprint for life

When Tsao was a child growing up in Hong Kong, his mother worked in garment manufacturing before retraining as a private chef. He remembers sitting in the kitchen with her and his older brother, helping to prep dinners – perhaps chopping vegetables or folding hundreds of dumplings: “We’d have this streamlined factory process, working quickly and precisely with our hands.”

He returned from university in the UK in 2012 with added appreciation for his culture. “It gave me fresh eyes,” he says. “I appreciated my city as an outsider might, cherishing its cultural heritage and crafts.”

Naturally creative and curious, he experimented with many media – paper lanterns, chops, rugs and even frisbees. However, during a year spent working in the US in 2017, it was his papercuts that garnered the greatest interest. “It really resonated with people. They found it refreshing to see traditional Chinese elements with contemporary design.”

Credit: Elvis Chung

Tsao started papercutting using knives, but purchasing a cutting machine in 2021 allowed him to mass-produce his work and has helped him to swap his career in architecture for art. He demonstrates how after drawing a new design, he’ll scan the pattern into his computer and send it to the machine, which turns his visions into reality. For Tsao, preserving this tradition doesn’t mean sticking exclusively to the old ways – it’s about knowing where its core values lie.

As we leave his Wan Chai studio on a rainy afternoon, Tsao returns to discussions with neighbours about the next opportunity to beautify their home. It’s safe to say that Tsao has found his calling – preserving the past while carving out fresh possibilities for the future.

Credit: Nick Tsao

3 of Tsao’s favourite projects

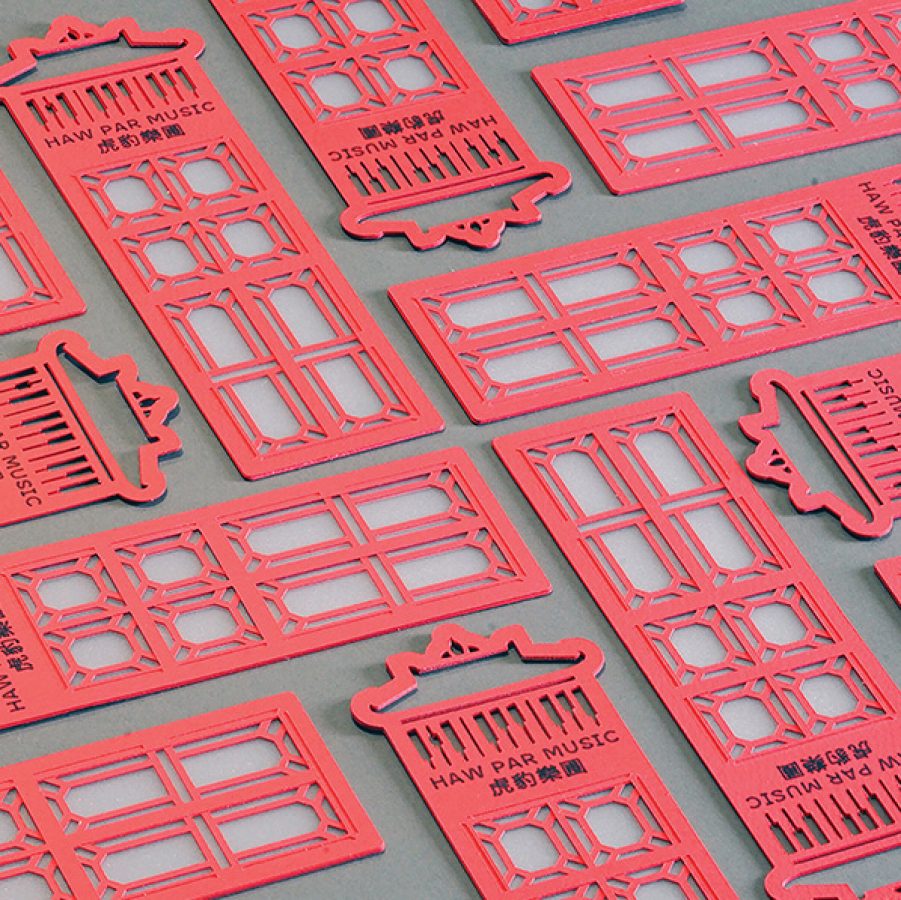

1. Sound design

“These bookmarks for the former Haw Par Music school took inspiration from the architectural details of the historic Haw Par Mansion: its stained glass windows, gilded coffered ceiling and cloud motifs on its moon door.”

Credit: Elvis Chung

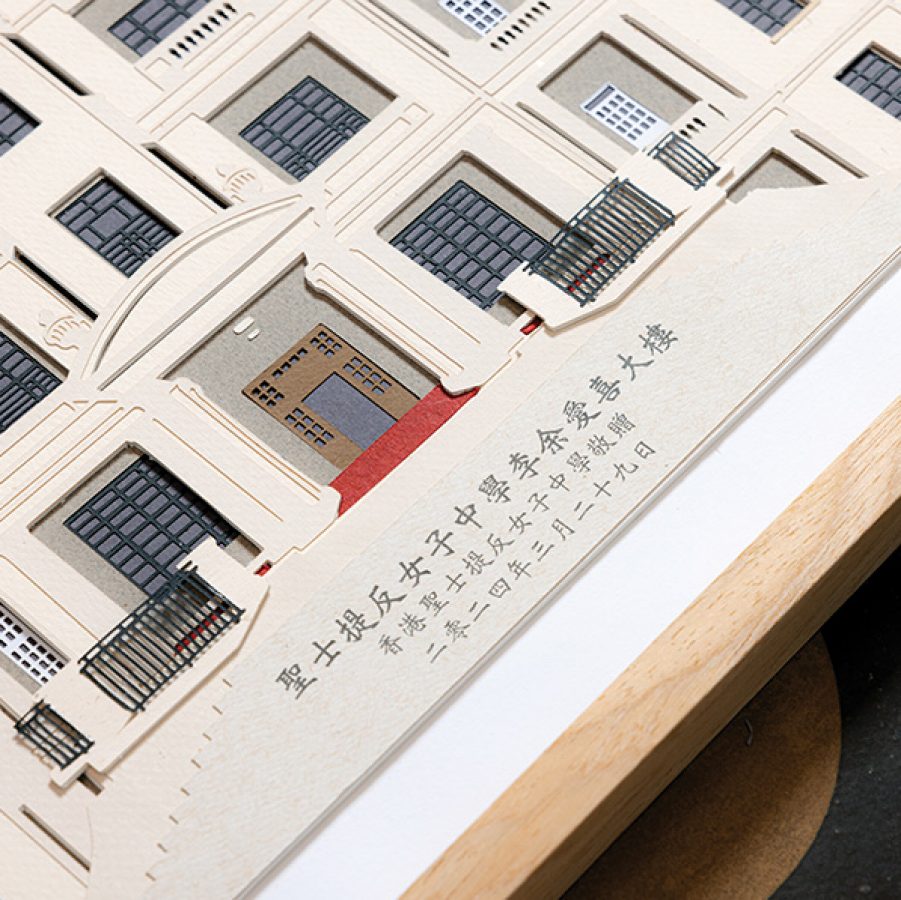

2. Top of the class

“For St. Stephen’s Girls’ College, I crafted an eight-layer recreation of its 100-year-old main building’s façade. I also made paper versions of its uniform, which were handed out at an anniversary event.”

Credit: Nick Tsao

3. Large scales

“An insurance company asked me to decorate the lobby of their office for the Year of the Dragon. Over two weeks, I made a continuous eight-metre scroll and cut it on the floor of my apartment by hand.”

Credit: Elvis Chung

Behind one of Wan Chai’s most fascinating landmarks

The Grade I-listed Blue House was built as a four-storey shophouse in the 1920s on the site of a former hospital. Its timber floors and staircases and cantilevered balconies make it one of the best-preserved tong lau, or tenements.

In 2017, the charity St. James’ Settlement revitalised the complex and rented some flats as part of a co-living concept, requiring prospective residents to submit an essay and be interviewed.

There are two rules: you must live here and contribute to the community in some way. Tsao originally visited out of interest in its design, but ended up applying for a flat, moving in during 2022. His contribution is designing the layout of decorations during festivals, such as Mid-Autumn and Christmas, most recently installing 600 hand-painted lanterns.

“In Hong Kong, there are very few historical buildings you can live in,” he says. “It’s about nostalgia and community more than anything, knowing neighbours by name and having meals with them. That’s more important to me than the architectural features.”

More inspiration

Hong Kong travel information

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English