The amazing story of Japan's freediving women

Tightly bound in a patterned skirt, white tunic buttoned to the throat, headscarf tied neatly, I’m ready to go diving. The wind is blowing a gale and the temperature is hovering around freezing.

Fortunately, I’m not getting in the water. Rather, I’m spending time with some of Japan’s hardiest women, the Ama divers of Osatsu, a town on Matoya Bay in Ise-Shima national park, two hours from Osaka. But before I can learn about their history and sample the sub-aqua treats they’ve foraged while freediving, they insist I get dressed up in the kit they use to go out diving. It’s a rare privilege. Men don’t get to do this job and the ladies take great delight in pointing and laughing at this gaijin with a beard in one of their traditional outfits.

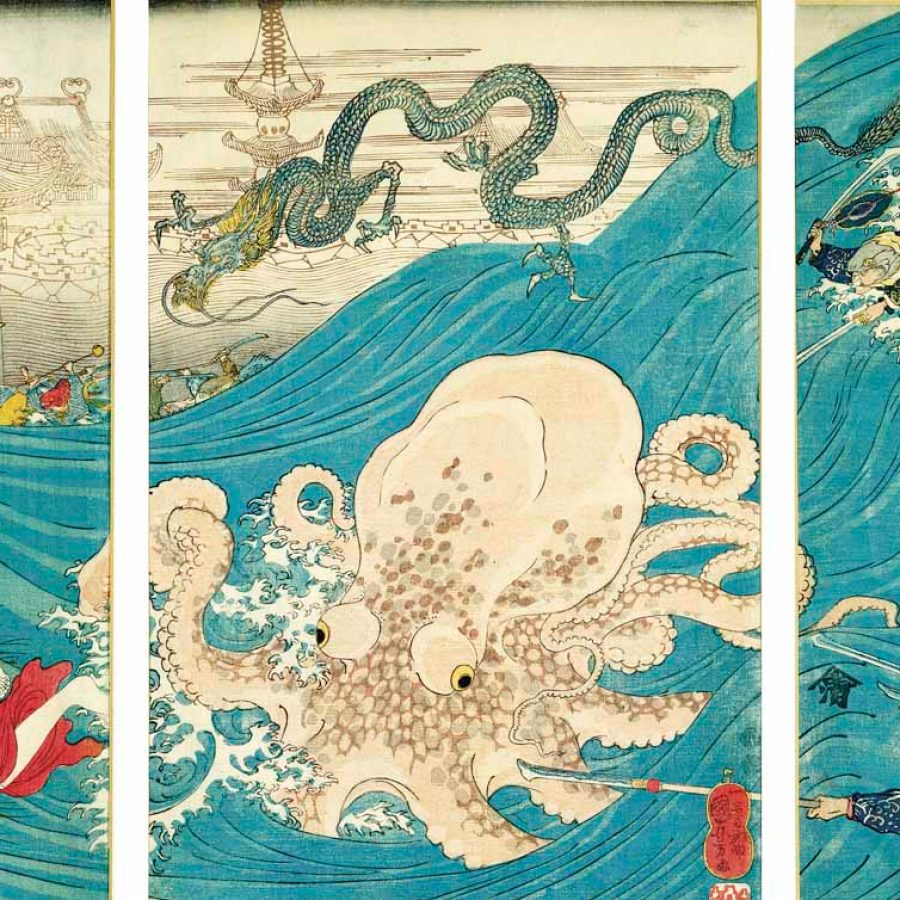

Ama divers (literally, ‘women of the sea’) have been working these waters for 2,000 years. The first reference to the Ama appears in Man’yoshu, an eighth century collection of poetry, while images of the women, naked from the waist up – they didn’t adopt the white cotton tunics until the early 1900s – appear in 18th century ukiyo-e prints. It’s only since the 1970s that they’ve taken to trussing up in wetsuits to protect themselves from the brutal cold of the Pacific off this stretch of southern Japan.

Credit: Look Bildagentur der Fotografen/ Alamy/ Argusphoto

Life for the Ama centres around an amagoya, a small wooden hut where benches line the walls and a fire burns in the centre of the room. The flames are there for them to both warm up and cook the abalone, crab and sea urchins they dive to depths of 10 metres to collect.

At the heart of this amagoya is Reiko Nomura. At 85, she’s the oldest of the eight women who work here and only stopped diving when she was 80. She started work aged 14, the fourth generation of her family to become an Ama diver. Women can’t just become Ama divers: it runs in the family. But now the young are turning their backs on this traditional way of life thanks to the lure of Osaka, Kyoto and Tokyo. Five years ago, there were 1,100 such divers in Ise-Shima alone. Now there are 800.

Credit: Go TABINUKI/ Mother Nature Inc

With fishermen sweeping up much of the remaining catch, it’s hard not to feel that the Ama are living precariously. But sipping tea in their amagoya, the smell of charcoal-grilled fish filling the room, you wouldn’t know it. Perhaps it’s the fact that they have a steady stream of visitors to dress up and cook for, but the women here are friendly, relaxed and keen to share their past.

‘Men can’t do our job,’ says lead diver Matgue Okano, proudly. ‘They don’t have the same body fat as women and can’t stand the cold.’ Instead, the man’s job was, and is, to sit aboard a boat from which a rope is attached to a diver, who makes for the seabed with a knife, surfacing to throw her catch into a floating wooden bucket.

When the catch is cooked, it’s unquestionably the best seafood I’ve ever tasted. The women who’ve tended the coals watch on as I scarf down abalone, followed by clams scorched in their shells, oysters and sea cucumber.

Credit: The Asahi Shimbun/ Getty Images

Ama culture is steeped in superstition. Before each dive, the women knock on the side of the boat or the wooden bucket, and recite a short mantra. While I eat, Matgue fills me in on some of the idiosyncrasies of this particular amagoya. ‘We don’t dive on the second or fourth Tuesdays of the month. Or on the 7th or 17th.’ I ask why: past accidents. Many Ama can recall at least one dive that came close to being their last. It’s a sharp reminder that holding your breath for upwards of a minute to dive to the seabed can truly be a matter of survival, rather than just an enjoyable aside for visitors.

The benefit of visitors is in helping to preserve this culture. During the G7 summit held in Ise-Shima in May 2017, local officials organised Ama diving demonstrations for visiting dignitaries, with the hope of getting Ama divers included on Unesco’s list of intangible cultural heritage.

The Ama are the epitome of the Ise-Shima peninsula. This area wears its localism and history with pride, especially at Ise-Jingu shrine. Japan’s most sacred Shinto shrine, just a short drive inland from the coast, has a history dating back to the third century. The place teems with visitors as I bow at the imposing torii gate at its entrance and cross the bridge into an ancient forest of cryptomeria trees, some 800 years old. The two shrines at its heart, Geku and Naiku, are the focus for the visiting pilgrims – 30,000 today alone. Shinto priests lead women in kimonos to altars out of bounds to regular visitors, who watch in respectful silence.

Credit: V&A Images/Alamy/Argusphotocredit: V&A Images/Alamy/Argusphoto

‘These women have paid a lot to make their offerings to the deities,’ says my guide, Midori. ‘They are praying to the gods for good luck in business.’

Midori bows deeply and I follow her back through the trees. As we walk, she explains that the temples here are rebuilt every 20 years, according to Shinto tradition. ‘The offerings of the women in kimonos and many others help to fund the maintenance of this sacred space,’ she says.

Ise-Shima’s traditions don’t just start and end with Ise-Jingu and the Ama. Late that night, after deciding against heading for the overwhelming light and din of Osaka, I sit back in an onsen at an old-style ryokan in the coastal town of Toba. Snow falls as I soak my bones after a day of immersing myself in local culture. Japan’s respect for the old, for its traditions, runs deep here. The further you get from the city, it seems, the more its ancient rituals reveal themselves. But as a cold wind whips in, I give a small nod of thanks to the gods at Ise that, instead of making me dive into the icy waters, they’ve led me here to this warm outdoor bath in one of Japan’s most overlooked outposts.

Hold your breath…

The art and science of freediving

Japan’s Ama divers are part of a broad fellowship who seek their livelihood beneath the waves, from the sponge divers of ancient Greece to the Bajau sea gypsies in Malaysia and Indonesia.

More recently, a way of life has segued into a sport, taken up by those who fully realise that freediving goes hand in hand with hazard.

It’s all possible because of something known as the mammalian dive reflex. When submerged in cold water, a series of automatic adjustments kick in: the heart rate drops to 30 per cent of normal and metabolism slows to maximise the available oxygen in the lungs.

During a descent, water pressure places the lungs in a vice, but on the way back up they expand, dissipating the remaining oxygen. If levels drop too low, and not enough moves into the bloodstream, unconsciousness swiftly follows.

Nobody knows better than Austrian Herbert Nitsch. In June 2012 he plunged 253.2 metres off Santorini, a world record. But his moment of triumph bordered on tragedy as he was stricken by decompression sickness, and had to be rushed to a decompression chamber, narrowly escaping severe brain damage.

Fellow free-diving champion Natalia Molchanova was not so fortunate, vanishing off Ibiza during a recreational dive three years later. However she is still widely remembered for her pithy verdict on her chosen career: ‘Freediving is not only a sport; it’s a way to understand who we are.’

Dive in deeper

For more information on organising a trip to Japan, visit the Japan National Tourism Organisation website. www.jnto.go.jp

Sea-Folk Museum, Toba

A museum dedicated to the area’s fishing history – including Ama diving – displayed through six buildings set on a beautiful seaside hill.

umihaku.com

Ama divers hut, Osatsu

This old-style divers’ hut in the town of Toba offers regular tours, with the chance to try on traditional costumes and eat fresh seafood cooked on hot coals.

amakoya.com

Todaya Hotel, Toba

With traditional tatami rooms, private onsen baths and chefs crafting fresh sushi from fish caught in the waters around Mikimoto Pearl Island, Todaya is perfect if you want to try something more local.

todaya.co.jp

Hero image: Yoneo Morita/ Sebun Photo/ Amanimages/ Argusphoto

Osaka travel information

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English