Gallery in the skies: in conversation with Wai Pong Yu

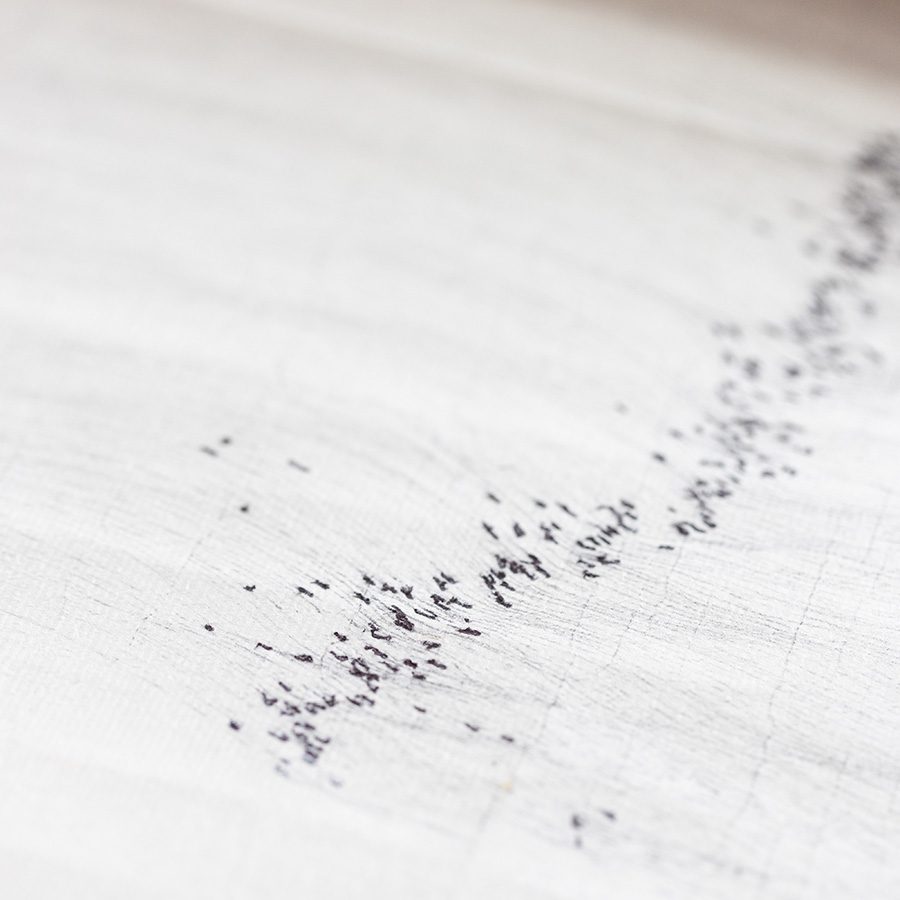

Watching Wai Pong Yu create his work is like watching a silent ballet. With the grace of a principal dancer, his hand guides a ballpoint pen across a vast sheet of paper. His movements fluid and his focus unwavering, he pauses to punctuate his strokes with deliberate dots before continuing. Wai transforms the act of drawing into an enchanting performance, inviting viewers to join him and witness his artistic vision unfold.

Wai's fondness for the ballpoint pen is rooted in its demand for focus. "This tool allows for the direct translation of thought to paper through the purity of line work,” he says. “Removing the need for colour considerations enables deeper concentration, while the permanent strokes of ballpoint pen art tell a story that cannot be altered."

Through his drawings , Wai explores both nature and humanity; A Rhythm of Landscape 38 and A Golden Bough 3 were inspired by the natural beauty of Hong Kong and Japan, respectively. Both works have been chosen to be part of our Gallery in the skies collection, set to adorn the Business cabins of the Cathay Pacific Boeing 777-300ER aircraft.

Credit: Mike Pickles

Credit: Mike Pickles

Credit: Mike Pickles

Since graduating from the Department of Fine Arts at the Chinese University of Hong Kong in 2006, Wai has dedicated himself to ballpoint pen art. “I’m fond of the tactile sensation of pen on paper, especially when working on Xuan paper,” he says. His creations straddle the boundary between ink painting and intricate sketching, comprising an endless web of lines that beckon the viewer closer to decipher the abstract and realistic elements woven within.

Unsurprisingly, Wai’s pieces have become a staple of the international art scene, celebrated and collected by institutions like M+ and the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, and showcased at Art Basel Hong Kong. He is currently absorbed in completing a large-scale painting scroll of roughly 2 by 3.5 metres, which will be exhibited in K11 Musea at the end of March.

Credit: Mike Pickles

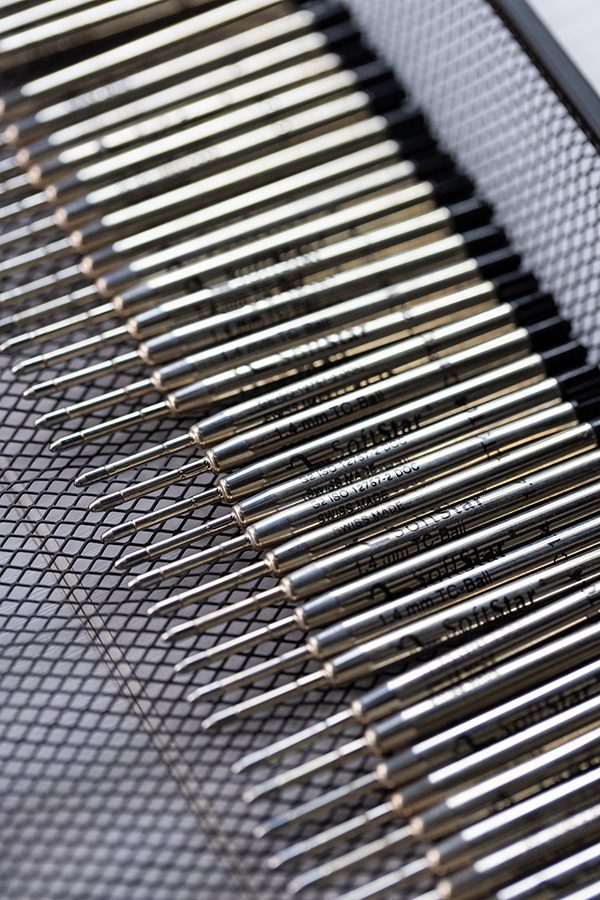

While ballpoint pens can be found just about anywhere, Wai opts for Swiss-made pens with thinner barrels and high-quality ink. “These pens are light-resistant, waterproof and bleach-proof,” he explains. “Meanwhile, the Xuan paper I use is made in Anhui province in the Chinese Mainland; it’s designed to preserve its quality for over a thousand years.”

For large-scale projects, Wai might stock up on hundreds of pens to ensure the uniformity of his work. To grasp the challenge of controlling such fine pens to achieve smooth, consistent lines, anyone need only try to replicate Wai’s technique. I attempt to do so myself, and it is indeed not easy – a further testament to Wai’s commitment to durability and precision.

A Rhythm of Landscape 38 was born from Wai’s deep connection to the natural landscapes of Hong Kong. As a child growing up in the New Territories, he would observe from his window the spectacle of rainfall passing over the mountains and learnt to perceive the silent communication between all things. "Whenever rain covered the entire mountaintop, a mist would drift among the forests,” he recalls. “This dialogue between the mountains and the rain seemed to narrate the feeling of living through changing times."

Always tuned into his environment, Wai found that during the pandemic his works became influenced by what was happening around him. "Daily essentials for people in Hong Kong, such as alcohol and bleach, became incorporated into my work. Ink turns purple when rendered with alcohol, while bleaching it creates a sense of void. Finally, I would sand off some lines to produce a feeling of memories that are both present and distant."

Credit: Mike Pickles

He adds: "my work is like my diary, with lines recording the conversations and thoughts of my heart."

A Golden Bough 3 is based on a photograph taken by Wai’s friend, Anselmo Reyes, in the forests of Japan, using a camera that once belonged to Reyes’ late father. For Wai, the idea of the camera as a "magical device" for seeking inspiration, and the process of searching for an image to capture, recalls a particular myth: it revolves around a prince who must obtain a golden bough to find his deceased father's spirit and regain the courage to lead his people. Similarly, Wai hopes that through this work, he too can find courage, hope and dignity.

Many artists prefer to work in solitude, but Wai keeps the doors of his studio open, inviting onlookers to become part of his creative process. Recently, during a two-month artist residency in Wuhan, he took part in a painting project that involved conversing with the public. "It was an open-hearted process, during which I actively listened to stories told by the audience, feeling their emotions and expressing my inner thoughts through my brushstrokes.

Credit: Mike Pickles

“In a gallery, it isn’t only artworks themselves that are important; the discussions of the audience can also become part of the work."

Regarding the debut of his artwork high above the clouds, Wai expresses his joy. "I'm delighted,” he says. “Displaying work in the air is quite intriguing. I feel that being in a high-altitude state of mind is another level altogether, one especially conducive to creativity.”

Wai hopes, he says, that when passengers see his work, they imagine themselves as tiny droplets in the vast sky, like the lines and dots in his drawings.

More inspiration

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English