Meet creatives remaking Chinese design aesthetic

“An unexpected spatial moment, a sudden shift of scale, a unique twist on a classic form, a new interpretation of a traditional element.”

That, says Lyndon Neri, is how to design.

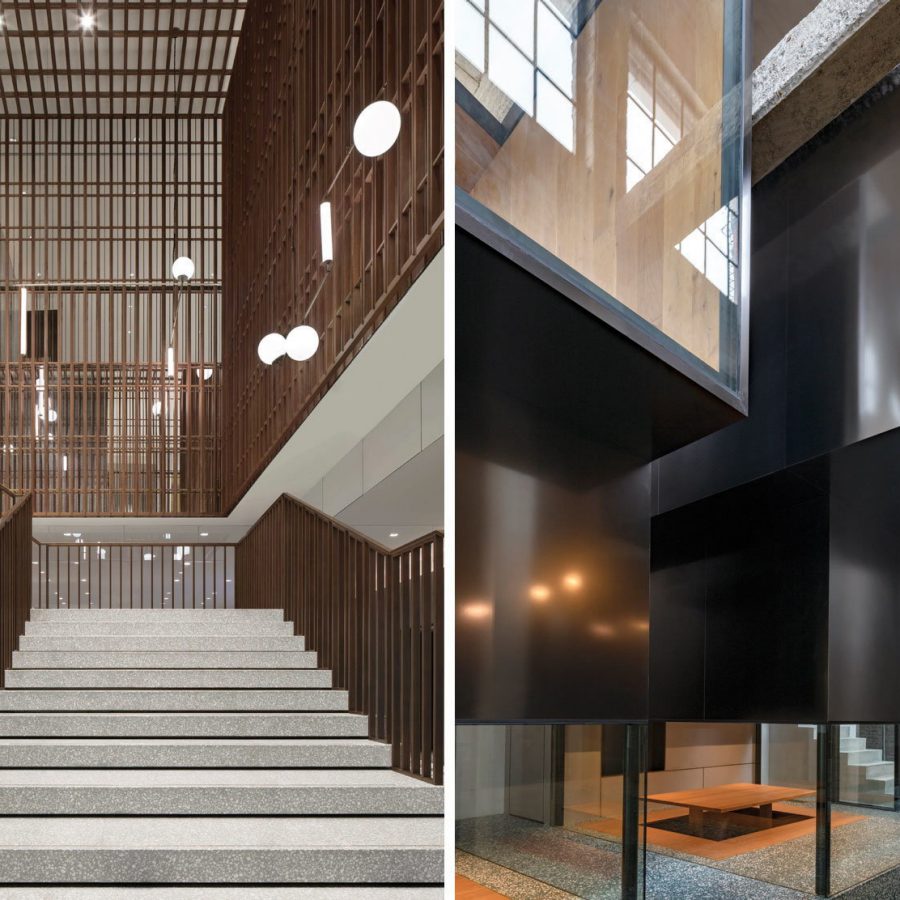

Credit: Andrew Rowat/Neri&Hu

He’s talking about how he approached two of his latest projects: the Shanghai Edition and Sukhothai Shanghai hotels, both of which opened in 2018. The Filipino-Chinese architect is the co-founder of Shanghai-based firm Neri&Hu , one of China’s hottest architecture and design practices. Formed in 2004 by Neri and his partner Rossana Hu, the pair have made a name for themselves with their modern, minimalist, concept-led approach.

Credit: Pedro Pegenaute/Neri&Hu/Sukhothai Shanghai; Dirk Weiblen/Linehouse/Tingtai Teahouse

It’s not just them, of course. Take a look around any first-tier city in China and you’ll find apartment complexes, office towers, hotels and even whole neighbourhoods being created.

Increasingly, architects and designers are injecting distinct aesthetics and elements from the surrounding environment into their work – crafting a brand new architectural design language.

Lu Hao, president of Hangzhou-based architecture firm GOA , describes contemporary Chinese design as “an integration and development of traditional residential culture, accumulated over thousands of years of history, and which conforms to the geography of our country and shapes the aesthetic psychology of our people.” In other words, it’s an evolution on what’s come before, a school of design referencing its own past.

Credit: Courtesy of GOA

Credit: Eric Leleu

For Alex Mok, co-founder of Shanghai-based Linehouse , that interplay of old and new is vital. Her firm is behind Tingtai Teahouse in Shanghai’s M50 arts district, a cutting-edge take on a traditional teahouse featuring slick glass-walled rooms that seem to float in the middle of a factory space.

For this project, her team stripped down the space completely to reinstate its original industrial identity, before adding warm wood and cool, contemporary glass. “It’s important to make the existing structures and new architectures flow together,” says Mok.

Credit: Pedro Pegenaute/Neri&Hu/Aranya Art Center

Besides old versus new, there’s also man versus nature. Outside China’s major cities, architects are integrating natural landscapes into their work. At Alila Wuzhen , GOA integrates elements of nature and Chinese cultural history into a luxurious, modern hotel space.

“Our design philosophy is always about shaping the experience,” says GOA’s Lu. Alila Wuzhen’s layout reflects the maze-like lane structure of classical Chinese villages – albeit “simplified by using abstract architectural elements.”

Credit: Dirk Weiblen/Linehouse/Tingtai Teahouse

Neri&Hu’s Aranya Art Centre in the port city of Qinhuangdao, Hebei province, is another merging of nature and mankind. The newly opened multifunctional art space appears at first to form an uncompromisingly solid silhouette in softer surrounds. But that structured, latticed exterior contrasts with a round, open-air amphitheatre on the inside – including a central section which can be flooded to form a water feature.

Credit: Pedro Pegenaute/Neri&Hu/Tsingpu Yangzhou Retreat

Clever compositions like these are also found in the firm’s design for the Tsingpu Yangzhou Retreat , which incorporates the surrounding landscape and structures to unify repurposed buildings in a formation inspired by traditional siheyuan courtyard homes.

Credit: Courtesy of GOA/Alila Wuzhen

As such, it would be easy to conclude that China is in the grip of an architectural renaissance. But given the country’s vast size, making any sort of generalisation about the state of Chinese architecture is tricky, warns Lyndon Neri. He says that Chinese consumers run the risk of being overly influenced by global design trends. “People are not being critical about what they see and use,” says Neri. “So regardless of good or bad, appropriate or inappropriate, it is all being taken in. We are now at a stage where consumers are digesting all of these new influences and trying to find an identity of their own.”

“Having said that,” Neri&Hu co-founder Rossana Hu adds, “there is a new generation of creatives here who are doing amazing work by exploring issues, materials and working with technology.”

Credit: Courtesy of GOA/Alila Wuzhen

Linehouse’s Mok agrees. “Here, possibilities are so open for what you can do,” she says. “From the suppliers to the artisans, the amount of customisation is great. You don’t get that anywhere else.” Scale, customisation and the imagination can run wild in China. The hunger is real: for new interiors, new architectures – and a new Chinese aesthetic.

Credit: Pedro Pegenaute/Neri&Hu/Aranya Art Center

More inspiration

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English