Exploring South East Asia with Stamford Raffles

Anyone who travelled with Stamford Raffles would have found him lively, agreeable company but hard work. The British statesman was interested in too much, wanted to know everything and believed in knowledge, education and civilisation as only a poor boy who has had to fight to experience any of them can.

We know him as the founder of Singapore – but our journey begins in Penang, northwest Malaysia, in 1805. There, he worked for the East India Company (EIC) – and learned to detest the company and its ways.

Credit: Alamy

Credit: Alamy

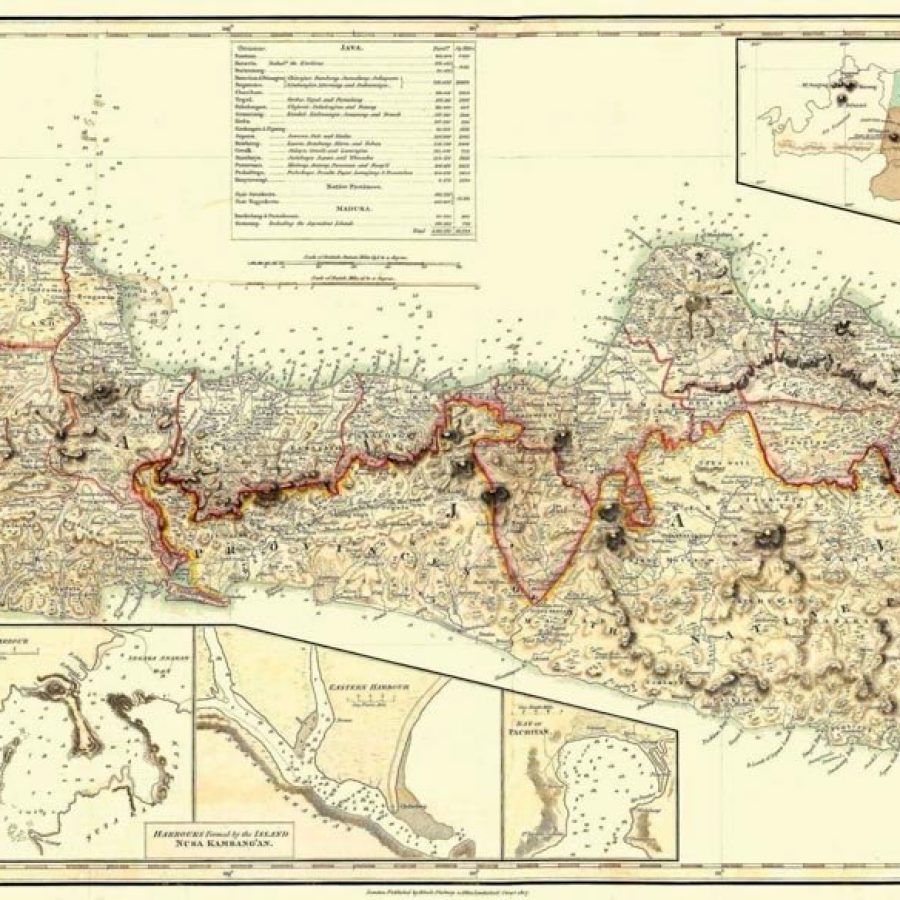

Java was the great love affair of Raffles’ life and our greatest adventure was the invasion of the Indonesian island in 1811 to stop Napoleon using it as a base. The battles were bloody, and Raffles worked round the clock to reorganise and reform, always asking questions and embarking on great treks across the island. He found the beauty of Java’s nature and royal courts breathtaking. In later years, he would drag his wife – heavily pregnant – hundreds of kilometres through the Sumatran jungle just because he wanted to ask the Batak people whether they really were cannibals. Always, he wanted to see for himself.

On a trip to Bali, he invented the idea that it was Southeast Asia’s ‘living museum’ – a view still sold to tourists. Then, in revealing and surveying Borobudur, central Java’s huge Buddhist temple, he made known one of the wonders of the world. Everyone on his journeys would have been weighed down with flora and fauna, textiles, carvings and weapons that he collected – not just as souvenirs, but as evidence in his argument that Java was one of the world’s great civilisations and therefore deserved the ultimate honour of being retained in the British Empire after the defeat of Napoleon.

As an unrepentant imperialist, he has received a bad press and we always seek a low motive hiding behind Victorian declarations of high virtue. That’s partly his own fault since he often wrote to London in EIC terms about making money. But Singapore was not just grabbed; it was built according to plans he drew up himself and in the face of orders to the contrary. If we had accompanied him on his landing in 1819, we would have seen nothing except a pile of human skulls left by pirates and lots of rats. Yet the founder of one of the world’s great trading centres was the world’s worst businessman and everything he did lost money – for, at heart, Raffles was a true romantic.

Credit: Getty Images

You can be sure that, on those journeys, every evening at dinner he would talk your ear off about how to make things better for what he termed the neglected ‘little people’. He gets no monument in the UK – the EIC disliked him – but in Singapore it’s not just the Hotel, the Place, the Quay and the College that bear his name. The Raffles Institution, a school he founded for the education of locals, not just in British ways but in their own languages and cultures, is his true legacy. He always remained that little boy desperately convinced that education could save the world.

Nigel Barley is the author of In the Footsteps of Stamford Raffles.

Hero image: Getty Images

More inspiration

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Americas

- Canada - English

- Canada - Français

- United States - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English