The front lines of the art world’s colour wars

Colours possess a beauty full of meaning. The alarming crimson of blood, but the seduction of red lipstick. The calm of an azure sky, but the warning of blue police lights. And black, the absence of light, reminds us of our mortality.

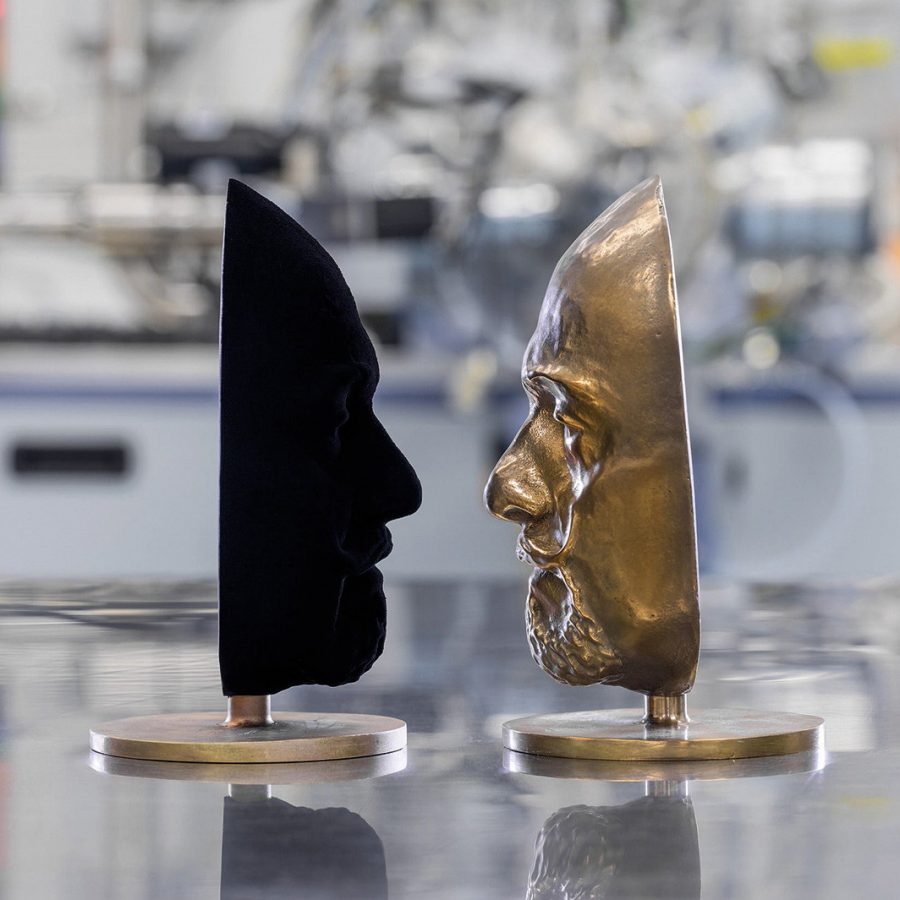

It’s a reminder that’s all the more present in the unique work of British sculptor Anish Kapoor. Encountering his totally black objects – so black they lose all shape and meaning – can be existentially terrifying. But Kapoor’s work isn’t just unique because of his ideas. It’s because of his product.

Credit: Surrey Nanosystems

In 2016, Kapoor acquired an agreement to be the only artist who could use the world’s blackest black. Named Vantablack, it was deliberately designed to be darker than any other known material. Objects coated in the substance, made from a ‘forest’ of vertical carbon nanotubes, lose their form – because to make sense of shapes, our eyes rely on reflected light. Vantablack absorbs that light.

‘Photons enter the structure and bounce around until they are absorbed,’ says Ben Jensen, chief technical officer of Surrey Nanosystems, which created Vantablack. ‘As a result, it’s confusing to look at; it warps our perception.’

Kapoor has since used Vantablack in several installations. His Descent Into Limbo, exhibited in 2018 at Portugal’s Serralves Museum , claimed Vantablack’s first victim: an Italian man required medical treatment after falling into the installation, which comprised a 2.5-metre deep pit painted with Vantablack so it looked like a two-dimensional disc.

To many artists, the idea that the extremely wealthy Kapoor was the only person able to use a material of such power was an affront.

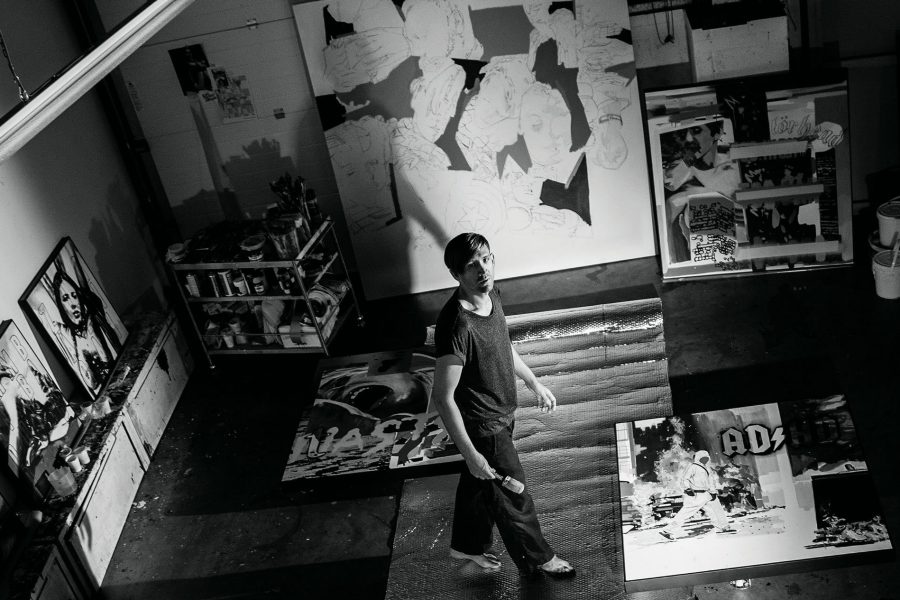

Credit: Vibrant Pictures/Alamy Stock Photo/Argus Photo

‘I thought it was really bad,’ says contemporary artist Stuart Semple. ‘It’s against the generosity of what art is. It affects the sense of possibility, if someone who has more money has exclusive access to something and can make something awesome out of it.’

It was as if Kapoor had stolen fire from the gods – and was keeping it all for himself.

Surrey Nanosystems’ Jensen is aghast at such suggestions. ‘People thought that somehow we had patented the colour black, which obviously isn’t true,’ he says. ‘We simply created a process for producing a super-dark material.’

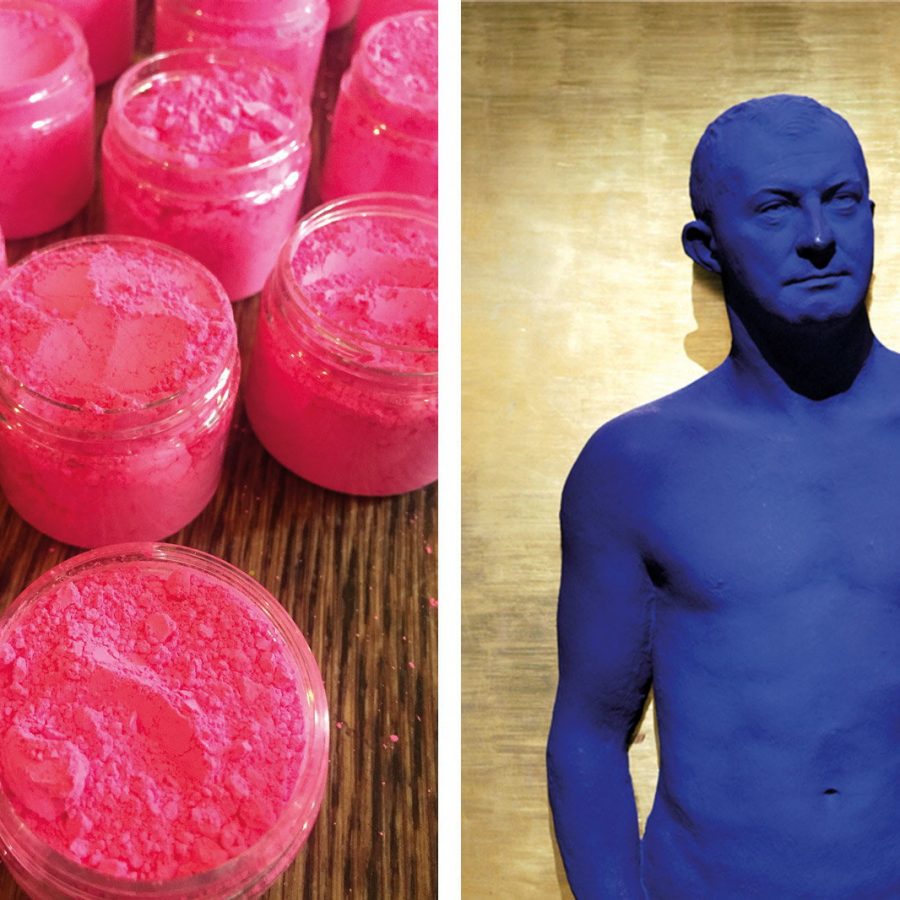

In retaliation against Kapoor’s chromatic coup, Semple released his own pigment. Simply called Pink, and described as ‘the world’s pinkest pink’, he made it available online for £3.99 (HK$40) per 50-gram jar.

But there’s a catch: those who buy it are required to confirm that they are not Anish Kapoor, and that ‘To the best of your knowledge… this paint will not make its way into the hands of Anish Kapoor’.

Credit: Surrey Nanosystems

Kapoor soon got his hands on a jar. He posted a picture to Instagram of his middle finger covered in the substance, with the caption ‘Up yours #pink’.

As humorous as the feud might appear, the passions it stirred reveal that our relationship with colour is no laughing matter. As Kapoor later acknowledged in The Guardian newspaper, ‘The problem is that colour is so emotive – especially black.’

Colour is also lucrative. In 2018 the global inorganic pigment market was valued at US$16.8 billion, a figure that is forecast to almost double by 2026. Owning the rights to a new pigment is, therefore, a big deal. But colour is a tricky business.

‘Blue, for example, rarely exists in nature,’ says Mas Subramanian, Milton Harris Professor of Materials Science at Oregon State University – and the discoverer of an entirely new pigment. ‘You can see blue in eyes or in the feathers of birds – but it doesn’t come from pigments. It comes from light interacting with a nanostructure.’

Subramanian notes that French artist Yves Klein achieved fame and a measure of notoriety for his International Klein Blue (IKB) paint in 1960 – but contrary to popular belief Klein was unable to patent the mixture, partly because IKB is not a pigment but instead heavily reliant on ultramarine, originally obtained by grinding semi-precious lapis lazuli.

Left: Courtesy of Stuart Semple/CultureHustle.com; Right: Olivier Laban-Mattei/AFP

The bottom line is that many naturally occurring colours are too complex to be replicated, and have only been discovered through serendipity. Take Subramanian: in 2009 he asked a graduate student to synthesise a mixture of the elements yttrium, indium, manganese and oxygen in the lab furnace, in hopes of yielding a material that could be used in electronics. Instead, the professor was presented with a bright blue substance.

‘Louis Pasteur said “Luck favours the prepared mind”,’ says Subramanian. ‘I was fortunate enough to see it and realise what we had.’

Subramanian immediately applied for a patent for the compound, which he named YInMn (pronounced yin-min) Blue, after its chemical composition. The pigment is now mostly used in the US paint and coatings industry: YInMn Blue reflects infrared light far more efficiently than conventional blue paint, helping to keep buildings cool and reducing energy consumption. Australian company Derivan has also produced an artists’ paint using the pigment. Titled Oregon Blue, the paint is priced at a cool AU$196.99 (HK$1,000) for a 40ml tube.

For his part, Stuart Semple has continued producing his own pigments. His latest offering? The blackest black paint in the world, his own middle finger to Kapoor.

Black 3.0 acrylic paint was a collaborative effort with 1,000 artists, Semple says. They developed a pigment called Black Magick, adding a carefully selected mix of elements – including Fairtrade organic coffee. (‘We needed something to counteract the chemical smell,’ says Semple.)

To pay for the paint, he launched what became the second-most funded art Kickstarter in history, bringing in close to £480,000 (HK$4.8 million) from more than 10,000 backers. (On the page, a note reads: ‘By backing this project you confirm that you are not Anish Kapoor, you are in no way affiliated to Anish Kapoor, you are not backing this on behalf of Anish Kapoor or an associate of Anish Kapoor.’)

Black 3.0 is due to go on sale in September. Can such a paint ever be as dark as the ultra-hi-tech Vantablack, or as exclusive as YInMn blue? No – but perhaps that isn’t the point. Each of these innovations is just an alternate route, another one of the infinitely creative ways in which people try to address an ancient longing: the desire to master colour.

More inspiration

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English