Amazing art pictures: see how these artists are transforming Japan's countryside

The village of Uwayu in Matsunoyama, Niigata prefecture, about 200 kilometres northwest of Tokyo, is the last place you would expect to find an avant-garde art installation. Overnight guests at Dream House, set in a 100-year-old traditional minka farmhouse, don a sleep suit that matches the colour of their room, sleep in a coffin-like ‘bed’ designed for dreaming and inscribe their dreams in a ‘dream book’.

This installation, created by 71-year-old Serbian performance artist Marina Abramović, is part of a growing trend of public art aimed at reviving Japan’s rural areas – some of which are fast losing their young to the cities, while others could use a boost after natural disasters.

Credit: Richie Chan / Shutterstock

Five stunning public art pieces in Japan

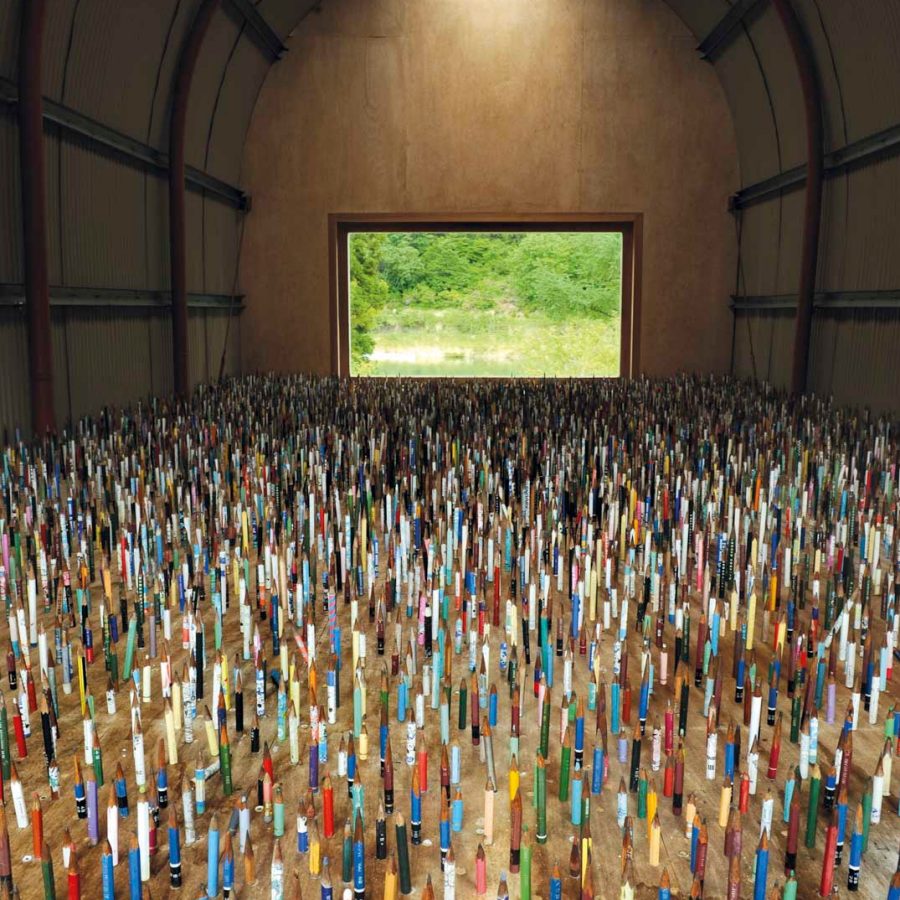

Abramović’s intriguing Dream House was created for the inaugural Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale in 2000, as part of a series of contemporary art installations by Japanese and international artists designed to reflect the rural environment and culture. Artworks are scattered throughout 200 villages – in abandoned buildings and schools, forest clearings and rice fields – encouraging visitors to explore remote areas.

The eclectic collection includes sculptures like the wildly colourful Tsumari in Bloom by Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama, and architecture such as Mudmen, a small but beguiling soil-concrete sculpture by Tokyo-based architect Jiro Ogawa, built by a river and featuring human-shaped floors, walls and ceiling.

This year’s Triennale (which runs until 17 September) unveiled 160 new works including a special exhibition in the Echigo-Tsumari Satoyama Museum of Contemporary Art, where 30 architects and artists created architectural designs in prefabricated mobile spaces three metres square. The exhibition is the starting point of a long-term initiative to revitalise the central area of Tokamachi City by embedding small spaces into existing empty houses and shops.

‘The endeavours in Echigo-Tsumari have inspired other regions, not only in Japan but also abroad,’ says curator Fram Kitagawa, who is also head of the Art Front Gallery in Tokyo’s Daikanyama, and a driving force behind the Setouchi Triennale and the Japan Alps Art Festival. ‘Their work functions as a device to expose and highlight the power of the sites and landscapes they inhabit. Through their work, the inhabitants rediscover the resources of their region and regain their pride in living there. Every place has such potential. What we have done in Echigo-Tsumari can also provide hope for many other regions.’

Credit: Jeremie Souteyrat

Other prefectures in Japan have realised the benefits of revitalising rural communities through art. In Kagawa prefecture, 12 remote islands in the Seto Inland Sea joined forces to launch the Setouchi Triennale in 2010, making the most of their extraordinary natural location to invite artists from all over the world to create site-specific works.

The event encourages artworks and projects aimed at revitalisating the local area. The organisers provide training and support, helping locals benefit through supplying food, drink and accommodation, and sharing their regional culture such as bonsai (Kagawa prefecture produces 80 per cent of the country’s pine bonsai). The 2016 edition drew more than a million visitors from Japan and abroad.

One of the most popular attractions in the Seto Island Sea is the Tadao Ando-designed Benesse House Museum on Naoshima Island. Rooms are decorated with works of art, and the numerous permanent installations include Yayoi Kusama’s gigantic outdoor Red Pumpkin at Miyanoura Port, and the Naoshima Honmura Art House project, which restored seven traditional houses, temples and shrines into art spaces. The highlight is Hiroshi Sugimoto’s elegant redesign and restoration of the serene Go’o Shrine.

In Nagano prefecture, the inaugural Japan Alps Art Festival ran last summer in Omachi, showing around 40 artworks. The festival will be held every three years and artists are invited to use local materials and explore cultural heritage in their work.

The same approach has been adopted in Tohoku, the region devastated by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, where the Reborn Art Festival blends art, music and local food. Held from July to September on the Oshika peninsula, close to the earthquake’s epicentre, the festival features masterclasses from Japan’s top chefs and local artisans, and live bands.

The artist Tatsuo Miyajima was in the Kanto area when the earthquake and tsunami hit, and was a volunteer during the relief efforts. His Sea of Time exhibit commemorates the victims, with LED lights at the bottom of a pool displaying a repeating countdown from nine to one, symbolising death and rebirth. Other poignant pieces included French street artist JR’s trademark photo booth installed on the hill of Hiyoriyama, where inhabitants of the Ishinomaki peninsula sought shelter during the tsunami.

The city of Odate in northern Honshu has also been inspired by the success of public art. Since 2007, its ZERO DATE project holds cultural events in abandoned shopping arcades and the surrounding countryside, encouraging visitors to engage with the local culture through exhibitions, a vibrant arts programme and a community cafe.

And since 2014, the Dogo Onsenart festival held in Matsuyama, on the island of Shikoku, has revitalised Japan’s oldest hot spring resort by inviting artists to transform hotel and ryokan rooms into art installations. Graphic designer Shin Sobue transformed one guestroom into a three-dimensional book, pasting the walls with the novel Botchan, based on its author Natsume Soeseki’s stay in Matsuyama.

Public art is not a panacea for the deep structural challenges that Japan faces. These creative initiatives have, however, highlighted the benefits of a more inclusive cultural landscape. It’s one that should help shake off the physical legacy of decline, and drive cultural tourism to remote areas.

More inspiration

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English