How AndBeyond is redefining the safari experience in South Africa

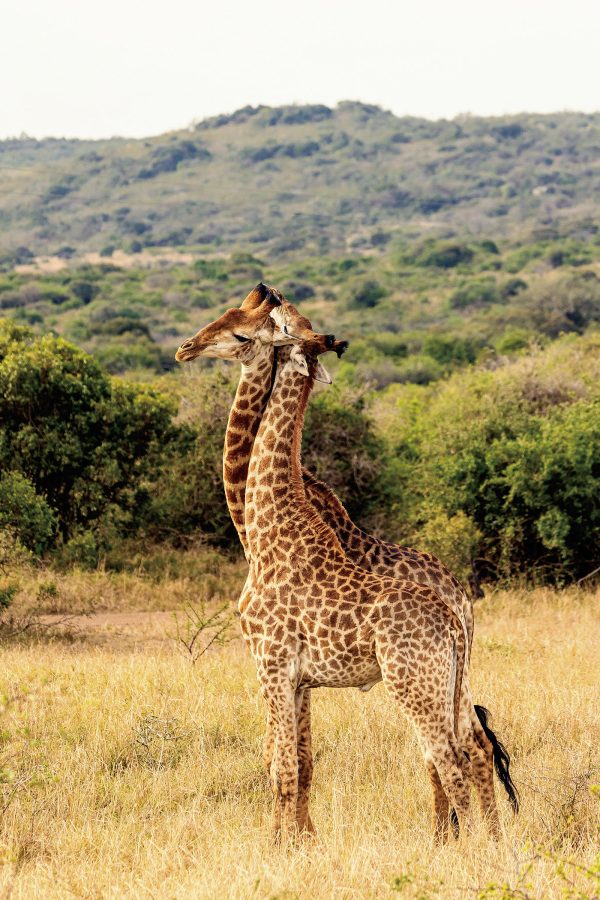

The sun rolls high through the sapphire sky at AndBeyond Phinda Private Game Reserve . Giraffes stretch above the treeline. An elephant bull snaps branches and stuffs them into his mouth. A hippo bellows from a pool. Wildebeest and impala roam in droves as dung beetles scurry across dusty tracks. From each dew-drenched spider web to every mud-caked rhino, we drink it all in.

We’re three hours north of Durban in the lush northern KwaZulu-Natal region. Phinda spans 286sq km and seven habitats, from wetland to sand forest, offering safaris that set the standard for conservation.

Credit: Eliud Kwan

Credit: Eliud Kwan

Credit: Eliud Kwan

On arrival, guide Gem Louw hands us a beautifully illustrated journal of Phinda’s flora and fauna. She’s at the wheel of our safari vehicle, with tracker Bongumenzi “Menzi” Dumsani perched on an elevated seat. Both grew up nearby and know this land intimately. Our car bumps and veers thrillingly over dirt tracks and, within a few minutes, we’ve had our first sighting: a trio of white rhinos – two females in oestrus and a hopeful male, repeatedly rebuffed. We wonder, don’t you know how endangered you are?

South Africa is home to the majority of the world’s rhinos, which are slaughtered in their hundreds each year for their horns, sold on the black market. According to conservation manager Dale Wepener (also a warden of the Munywana Conservancy, upon which Phinda sits), to keep this constant threat at bay, Phinda employs a three-pronged anti-poaching approach: intelligence networks, surveillance teams and dehorning.

Credit: Eliud Kwan

Credit: Eliud Kwan

The latter, a painless process, involves tranquillising the animal from a helicopter – an experience guests can join – then sawing off most of the rhino horn, which regrows like a fingernail. According to the conservation charity Save the Rhino, the practice was crucial to achieving a poaching decline of nearly 30 per cent last year in KwaZulu-Natal, the hardest-hit province, compared to 2023.

Credit: Eliud Kwan

Before 1990, Phinda was depleted farmland. AndBeyond’s founders bought it, reintroduced large mammals and created a conservation zone funded by low-impact tourism that benefits local communities. Guests travelling from around the world are vital to this model, despite the environmental cost of their journeys. “If the safari industry didn’t exist, the environment that attracts it wouldn’t exist. Phinda would quickly return to farmland,” says Wepener. “People stay here so we can maintain the wildlife reserve. By 2030, we aim to double our conservation footprint, which will only be possible if guests keep coming.”

Credit: Eliud Kwan

Credit: Eliud Kwan

Credit: Eliud Kwan

Phinda, in Zulu, means “the return”. Menzi teaches us phrases like ninjani – “How are you?” His ability to spot wildlife borders on the supernatural: a flicker of hide, a shiver of leaves and we’re off in a new direction. “I know this land so well that I notice when something changes,” he says.

No sooner has Menzi told us this than he catches sight of three young cheetahs patiently preparing for a high-stakes hunt. Their bony frames are low in the long grass as they stalk a zebra foal. Then – like a shot, they’re off. “It’s hold-on-to-your-hats time,” says Louw, as she steps on the accelerator. The herd scatters, elders shielding the foal in a protective wall. The predators retreat to reconvene.

Guides carry rifles but the last time one was fired was 1998. “We have to love and respect the animals,” Louw says. “Everything is about respecting their nature and territory.”

Our guides are exceptionally knowledgeable. We learn that zebras are excellent parents, that impala form harems and that elephants go through six sets of teeth and communicate via stomach grumbling that vibrates through the ground. Nature’s symbiosis is everywhere: oxpecker birds feast on ticks clinging to giraffes; ants nest inside acacia thorns, defending them from herbivores.

“Life in the wild is very life or death,” Louw says, as she reveals a pop-up bar in the back of the vehicle for a mid-safari pitstop. Sipping Amarula-laced coffee and nibbling biltong, it’s hard not to feel spoiled by the experience.

Credit: Eliud Kwan

Credit: Eliud Kwan

Credit: Eliud Kwan

Phinda offers six luxury lodges. Phinda Forest Lodge and Phinda Mountain Lodge suit families, with pools, firepits and kids’ activities; Rock Lodge, carved into a cliff, is perfect for couples seeking solitude; Phinda Homestead, a sole-use villa for up to 10, comes with a private chef, boma (fire pit area), pool, gym and massage sala.

Guests enjoy two game drives a day – at dawn and dusk – tailored to the wildlife you most want to see. Back at the ranch, dining celebrates local ingredients and South African wines. Optional add-ons include sleepouts under the stars, conservation activities, tours of local Zulu villages (with funds going directly to the community) and trips to beaches in the Maputaland region for turtle spotting and scuba safaris.

One evening, after the sun melts into the horizon and the vast Milky Way sparkles overhead, our sharpened senses detect a sweet, musky smell. “Fresh kill,” says Louw, grabbing her radio. “Lions might be close.” We race into the darkness. The pride is at the reserve’s airstrip – a favoured dining spot. Phinda enforces a strict three-vehicle limit at sightings, so we wait in darkness, engine off. Then, Menzi sweeps a red light across the tarmac. Eight lions glow crimson in the gloom; bellies full, they’re sprawled docile. We, on the other hand, are left with hair stood on end in a primal response to being mere metres from one of nature’s most iconic predators. We see lions again during our stay – playing in grassland and lazing across ridges – but nothing matches that first spectral encounter.

Each night, we return to the lodge with our necks craned skyward, scanning for constellations, planets and satellites. Rising early and going to bed early, our circadian rhythm syncs with nature. On the final morning, we see those same three rhinos – the male still trying his luck. Their horns are growing back and will soon need trimming. They’re safe, thriving, as life’s wheel turns around them. That’s the beauty of Phinda: it reminds you of your place in the world. The return – in every sense.

Credit: Eliud Kwan

Credit: Eliud Kwan

Getting here

Phinda Private Game Reserve is 530km east of Johannesburg and can be reached directly by charter plane (Starlite Aviation), shuttle flight (Federal Air) or a seven-hour drive. The nearest commercial airports are Richards Bay and Durban, with AndBeyond transfers available.